One of the topics that will occupy all

our interests is who has walked this land before we were

here? This is

precisely what Archaeology is all about and why everyone is fascinated

to a

greater or lesser degree. Who has stood where you stand now? Who were

they?

What were they like?

I live on the South Coast of England,

look on the map below and you will see that I live just to the left of

the Isle of Wight in a place

called West Sussex. With my wife, I own a property in a town called

Worthing.

It’s not a big property but I have a front and back garden where, if I

want, I

can go and dig with no one to tell me “no”. Its mine and this land will

grow

things, produce food, make flowers and look after me and it all belongs

to me,

but every now and then I stop and wonder who has said this before? Who

has been

attached to, and nourished by, these few yards of good soil?

Map of

West Sussex

My piece of land has had people here

before, not just the people who owned the house before me but over the

years

and centuries even millennia. My quest was to find who they were, how

they

lived and are the hypothetical footprints still there for me to find.

The south coast of England is just north

of 51 degrees latitude and where I stand less than 1 minute west

longitude so I

virtually am on the prime meridian. It has a temperate climate and is

warmed by

the Gulf Stream so winters are not usually that severe, but this was

not always

the case. Over the last million years Ice Ages have come and gone and

although

the ice sheets have never quite reached here, quite often this has been

a polar

desert with no plants, animals or life of any kind. It is in this

sometimes

hostile environment that life has come and gone in my garden.

When early man first set foot on my

piece of land is a matter of conjecture but from finds at Pakefield not

that

far away we know that archaic humans were here three quarters of a

million

years ago. That’s 30,000 generations ago a period virtually beyond

comprehension. So did this early forerunner of man walk on my lawn?

Yeah I

would like to think so; it gives me somewhere to start. Somewhere to

put a

stick in the ground and take a small flight of fancy.

Since this far off epoch the ice has

come and gone 6 times, the Cromerian, Anglian, Hoxian, Wolstonian,

Ipswichian

and the Devensian glacial periods have all left their mark upon the

land. My

garden has only been able to support life for about 30% of the time in

all

these millennia but it is in these times of interglacials and

interstadials

that I know where to look where people used this bit of land I call

mine.

So where can I really start and

definitely say here someone lived and walked on my piece of land

To answer this I have to go back 485,000

years

Over many years, in an area about 15

miles to the west of me, many flint handaxes, like those from

Swanscombe, were

turning up in marine sands that were preserved and being quarried. The

geology

of the area showed that the sands were laid down on top of a beach at

the base

of a then 300 foot chalk cliff that extended 25 miles along the then

coast. The

area was a very large embayment that had been cut by a massive river

that would

in time form the Isle of Wight. A huge lagoon full of salt marsh and

grassland

had provided a suitable habitat for animals such as red deer, bison,

horses and

even elephants and rhinoceros. Into this area of plenty had come

Heidelburgensis

the forerunner of Neanderthal who lived well of the live stock and

plants of

this fertile landscape. The area had everything a hunter gatherer could

want

meat, fish, shellfish, berries and a good mixture of edible plants.

Eastern

face of the Swanscombe Hand-Axe Sculpture in Swanscombe Heritage Park,

NW Kent.

Sculptors David Robinson & Peter Greenstreet of GES Ltd, 2005.

Manufactured

by;

Bob

Hogben,

BH

Engineering.

Flint in the chalk cliffs provided a

ready available source of raw material for hand axes that were used to

kill and

butcher and as the site was repeatedly covered by gently flowing water

the

surfaces were sealed with fine silt that left activity untouched. The

preservation was so good that places where people crouched down to make

their

flint tools have been conserved with every flake discarded still in its

original position. In one place the outline of the knapper’s knees can

still be

seen outlined by the debitage.

So here was my first real encounter with

the peoples who I share the land with. A group of hunter gatherers who

killed

and butchered large animals and left their bones and tools where they

were used

The raised beach that was discovered at

Boxgrove extends from Portsmouth to almost my front door and is now

through

orthogenic movement in the last half a million years 40 metres above

sea level

and there has been a series of digs along its length where and when it

outcrops.

Biface

found at Boxgrove. More to be found at the

official Boxgrove website.

I teach illustration, planning and

section drawing at Sussex University and therefore get involved in many

digs

with the professional units as their site recorder. The Boxgrove

project (put

Boxgrove project in your search engine or Valdoe project or Slindon

Bottom) has

been extended and in my next chapter I will report on the digs and the

finds

Chapter

II Digging the Lower Palaeolithic

I must start with some geology to set

the scene. Following the Jurassic, 136 million years ago, the whole of

the

South of England was immersed in a shallow warm sea and this laid beds

of

various materials down starting with a series of clays called the

Wealden beds.

This was overlaid by the lower greensand then the gault marine clay and

upper

greensand and it was on these beds that the chalk was laid down. [editor's note: You can read more about

this, here: http://easyweb.easynet.co.uk/~gcaselton/fossil/fossil.html]

Chalk is a 98% pure calcium carbonate

although the lower “grey” beds can contain clay minerals, silt grade

quartz and

glauconite. The upper beds epitomised by the white cliffs of Dover

contain a

series of layers of flint that made the region such an attractive

proposition

for early man. These white beds, up to 1100 feet thick were laid down

very slowly

it is estimated at about an inch every thousand years. Subsequent

tertiary

folding uplifted the Downs into a dome and depressed what would

eventually

become the English Channel. In the last 64 million years further

folding and

subaerial erosion produced the present day structure and topography.

Sea erosion into this uplifted land

produced cliffs and because chalk is so friable the wearing away

continually

exposed the embedded flint that made beaches and pebble deposits.

In Sussex we have a series of “old”

beaches buried in places by tertiary deposits and exposed in others. It

is one

of these beaches that were being formed in the lower Palaeolithic when

early

man used it as a hunting and living area. Due to orthogenic movement

this

raised beach is now well above sea level at the 40 metre contour.

Near the tiny village of Boxgrove there

are quarries extracting aggregate and for a long time hand axes were

found that

promoted investigation into the site. The area is between two inliers

of chalk,

the Portsdown anticline to the west and the Littlehampton anticline to

the

east. The northern boundary is a relic buried cliff and it was at the

base of

this buried cliff that the beach developed. The south of England is

tectonically active so the relationship to present day compared to half

a

million years ago has somewhat changed. The cliff is still there but

now only

about 35 feet high and lies below a considerable amount of overburden.

In the last 10 years since the first

discoveries at Boxgrove bore holes have been sunk following the old

cliff line

sometimes up to 30 to 40 feet deep and at Slindon Bottom the ancient

beach

currently lies exposed so we now know where it is so since 2006 a

series of small

pits have been dug to sample the beach itself and the overlying strata.

Unless you are clearing a large area for

health and safety reasons trenches must not have vertical sides of more

than 5

feet (1.5 metres) so the first requirement for any excavation is a JCB

or

similar mechanical excavator. It is very easy to tell the depth in

terms of

ancient deposits as a series of sands and silts is very well defined.

The finds

bed is delineated by the residue of the salt marsh and decayed plant

life into

a layer called the Mg.Fe. layer (magnesium and iron) that is a brown

bed about

a quarter of an inch thick and looks for all the world like a

crème brulee.

This layer is all that’s left of the marshy horizon and its contrast to

the

bluish sandy silt above it is very pronounced.

A JCB

excavator.

Before we go into detail about the

raised beach itself and the archaeology let me relive for you the

latest

excavation at the Valdoe quarry to give a feel of what its like to dig

this far

back into the past. The position of the beach was known from a series

of bore

holes carried out the year before and the site itself is about 2 miles

west of

the main Boxgrove quarry.

Climate is what you expect but weather

is what you get and the first day did not let us down. Cold wet and

what can

only be described as miserable. We parked our cars just off the

Goodwood road and

started the quarter of a mile trek down a puddle path to the site. Bore

hole

information had revealed that we needed to go down some 3 metres (10

feet) so

the JCB had removed the overburden so the site descended in three steps

and had

stopped at 2.5 metres. The first job was to clean back the western and

northern

walls and expose the strata so a geological record could be made of all

layers

from the top soil down and to make safe the two intermediate platforms.

The

final cut was a trench 2.1/2 metres by 1.5 metres but the surface cut a

6 metre

square.

The geology of the site was quite

complicated with, from the top downwards, top soil and leaf mould and a

mixture

of top soil and gravel. Below this was a series of beds with

solifluction

gravel intruding into three separate dry valley deposits. Following

this was a

series of calcerous solifluction gravels and a broad layer of lower

brick

earth. Just above the MgFe layer was a thin white layer of chalky marl

and

below the various Slindon silts.

A look at

the stratigraphy mentioned above.

Finds were confined to the lower part of

the brick earth and the top of the Slindon silts. So the mechanical

digger had

ceased its operation in the solifluction calcerous gravel leaving the

last half

metre or so to be dug by hand.

Lower Palaeolithic finds are like gold

dust so the area was removed by hand trowel a quarter of an inch at a

time so

not to miss a single thing. And so began the lengthy process of

clearing,

tidying, examining the JCB spoil heap for sporadic finds and the dig

itself. No

shoes or boots were allowed on the exposed final surface and in the

confined

space only two diggers at a time could work kneeling on a pallet and

reversing

their position after every inch or so removal.

By now we were into day three and

arriving on site discovered that there was about 3 inches of rain water

flooding our trench. Before digging could resume lunch boxes were

pressed into

active service to bail out the site and car sponges were required to

mop up the

last of the water. Looking for the MgFe layer is a frustrating time as

you

cannot rush the dig and every now and then you uncover a hint of brown

that

just might be it, only to have your hopes dashed as it’s just a bit of

subsequently deposited material. I do not know about the Sun shining on

the

righteous but as the Sun did come out in the afternoon its arrival

marked the

first signs of the layer we were all looking for. Then the excitement

of a

find, each piece when discovered has to be photographed in situ,

measured, its

dip angle and orientation noted and then, and only then can it be

lifted.

Rain in

the excavated pit.

Cleaned

out.

I cannot adequately express the sheer

excitement of holding in your hand something that was made and has lain

there

where it was dropped 485,000 years ago. You hold it, look at it and

just know

you are the first person to touch this for half a million years. Then

even more

exciting in a small area four axe sharpening flakes, left where they

were

dropped when putting a new edge on an axe. You really had to be there.

Everyone

crowds round. Everyone wants the first look. Cameras appear. The bits

are

really tiny but they are so special. I can go on for hours about this

and

months later the moment is still vivid in your mind.

A

precious find emerges!

Never mind digging up a Roman Pot or a

medieval jug this stuff is 250 times older. I am sure you, when reading

this,

think I am a bit daft but let me tell you this is a real wow! moment or

should

I say a Wow! Wow! Wow! moment. Then its soil samples, photographing,

drawing

and recording, measuring everything in with the total station and

clearing up

and the start of the post excavation work.

The find

in context.

More finds!

The mechanical digger quickly fills in

all that work and we are back to the muddy path, the cars, the drive

home and a

very satisfying large scotch.

Pit at

dig's end.

I have no idea how many tons of material

has been removed and put back or how many hours of labour went into

that small

handful of flint but was it all worth it? For me an unequivocal yes and

would I

do it again, yes, because that’s archaeology.

So what do we know about this early

peoples and their environment. To answer that question we need to go

back to

Boxgrove.

100,000 years before the emergence of Neanderthal a

large brow hominid roamed this land. Descended from

Egaster, Heidelburgensis

with his basic flint tools was the master of all he surveyed. He

inhabited this

part of the world probably from the East across east Dogger Land that

would

later become Holland. The climate was easy and the land rich in

wildlife. Red

Deer were in profusion and so the living was good and it would be many

centuries before the onset of the Anglian Ice Age.

A small area in the South of England was

ideal for living as an embayment provided grass land sheltered from the

prevailing winds, salt marsh with a profusion of shell fish and a ready

supply

of flint outcropping from the chalk cliffs.

The main tool of the period was the hand

axe and over 300 were recovered from Boxgrove. These multi purpose

tools were

the Swiss

army

knife of its period and it is thought that they also may

have

had a social connotation as well as a hunter gatherer implement. Social

standing could have been signified by the perfect hand axe and sexual

display

was not ruled out. The living was a family gathering type grouping with

man,

women and child all belonging to a social network. The role of the

males would

have been very much the hunters but after the kill everyone would have

joined

in the preparation of the carcass and the amount of bone found with cut

marks

indicates a fairly sophisticated level of dismemberment with little

wastage.

The silt beds at Boxgrove were covered

with a fine deposit from slow flowing water so the preservation is

perfect in

every detail. Today things were still in the same position as they were

half a

million years ago when they were covered. A kill would have fed the

group for a

considerable period so there must have been time for teaching others

and being

with children that would have further added to the development and

survival of

the group.

There is not that much we can tell about

the day to day life of Heidelburgensis but it is just possible that a

crude shelter

was erected just next to where my garden shed

is today and was

the home

for about 20 people and I can just imagine dad and his two brothers

coming up

what would become my garden

path with a young deer and being greeted

with the

excitement of a good feast tonight.

We know really very little about Heidelburgensis

but if we were to meet him on the street today would he be out of

place. An

adult male was about six feet but much sturdier than today’s males. The

body

lacked prolific hair and the flat face and stereoscopic vision made him

very

much like us. The rib cage tapered towards the bottom of the abdomen

which indicated

that the gut brain ratio was in tune with modern man and this in turn

indicates

a full and nutritious diet. With his stone axe Heidelburgensis had

access to

parts of a kill that were the highest protein, bone marrow and the

brain. His

tools kit contained the right equipment to get into heavily boned areas

and

therefore it is not inconceivable that he was a scavenger of any kills

in the

landscape even after the larger carnivores of the period had finished

with

their carcasses. The legs of Heidelburgensis tapered inwards from the

pelvis

again indicating a totally upright stance and the shoulder joints had

full

mobility to perform many tasks including throwing, climbing and

carrying.

It can therefore be assumed that this

was like us in many ways and possibly washed, dressed and with a

haircut our

primitive man could walk down my street without turning too many heads.

This then was the forerunner of

Neanderthal and Homo Sapiens. Driven out of this part of the world by

the

encroaching ice as the world cooled. Millennia would pass before the

land would

warm up and recover its foliage and animals but as this came about a

“new”

intruder was on this land.

Chapter

3 Digging for Neanderthals

We now enter a long period where I must

speculate. These are the periods of Neanderthal.

I am surrounded by areas of Neanderthal

habitation the nearest being just along the coast to the West of me at

Barnham.

The south east corner of what will eventually become the England that I

would

recognise. This area is full of places where our enigmatic ancestor

lived and

died such as Swanscombe, Clacton, Lynford in Norfolk, Purfleet,

Thurrock and

Hoxne

Following the Boxgrove finds the Anglian

cold stage wiped out all life but following this the first signs of

Neanderthal

were around the Hoxnian interglacial at 400,000BP but were quickly lost

due to

the onset of the next ice age, in due time the Perfleet interglacial

dawned and

back came Neanderthal.

The millennia following showed the same

pattern over and over again until we come to 120,000BP and the

prolonged

Ipswician interglacial when we had one of the warmest periods of the

last half

million years. The trees, plants animals in profusion were here but no

sign of

early man. Why, when conditions were so conducive to habitation we had

a period

of non humans is unknown but it would not be until a short interstadial

in the

Devensian ice age do we find the local appearance of my early

neighbours. There

is some evidence that England may well have been an island in previous

periods

when sea levels rose following the ice melt but this is not conclusive

as it

may well have been possible for Neanderthals to cross the English

Channel as it

was then

What was my back garden like in these

periods of habitation when Neanderthal reigned supreme as top of the

predator

chain? Neanderthals had a large brain case, buried their dead and

produced a

very sophisticated tool kit so we can imagine that life was somewhat

structured. The development of thicker set bodies and the ability to

survive

in a colder climate would have greatly helped with the diverse extremes

of

climate.

Butchery marks on animal bones show a

developed system of co-operation as on the mainly grasslands a kill

would mean

fast dismemberment of the carcase before the smell of blood attracted

the large

scavengers and hunters that contested for game.

I like to think that the extended family

was much more of a well knit group than Heidelburgensis and in my minds

eye I

can see my back garden now in use as a hunting camp with all the family

active

in one way or another as dad and his brothers and perhaps an eldest son

bring

home the butchered remains of a deer or perhaps an even larger

quadruped.

We know from skeletal remains from

France and Germany that Neanderthal was an active hunter as injuries

and breakages

mended are commonplace so I like to think that exactly where I now grow

gooseberries the Neanderthal group collected for their meal before

sleep on a

balmy evening. I can just see them happy, well fed and relaxed

sharpening an

axe in preparation for tomorrows adventure

Each time there was a re-emergence of

Neanderthal the tool kit changed often for a more and more

sophisticated way of

manufacture. The final incursions between 60,000 and 40,000 during a

short

interstadial in the Devensian showed the development of the elongated

leaf

point and it is in this period that our next excavation took place.

A

Neanderthal tool kit (

Photo: Dr

Ralph Solecki).

To understand the setting we have to

look at the scenery and structure of the South Downs the southern

residue of

the chalk and other cretaceous beds uplifted and then worn away and

stand on

the outcropping of the lower greensand overlooking the wealden clay 200

to 300

feet below us. If we look to the south there is an undulating terrain

of the

gault clay and upper greensand and about a mile away the rise of the

escarpment

of the chalk downs rising steeply another 300 to 400 feet. To the north

there

is a wide sway of grassland with sporadic trees and in the very far

distance

there is just visible the outline of the chalk escarpment of the north

downs.

This lower greensand gives up a

wonderful vantage point to see game crossing the plain and

would have made an ideal spot to become the

base for living and camping. Today the view from this position is still

stunning and allows you to see at least 40 miles on a clear day.

It all started with John Hartley of London

a consulting physician and fellow of the Linnean Society who, when

retired,

decided to build himself a house in Sussex. The year was 1900. Whether

it was

ostentation or just the need for grandeur the house was somewhat of a

monstrosity complete with fake crenulations and battlements. Named

“Beedings”

the house was soon referred to as Hartley castle by the local populace

as it

dominated the crest of the escarpment of the lower greensand.

Beedings

"castle" (photo from Beedings

Project

website).

In laying out the foundations several

Roman finds were made including amphora, pottery and silver Roman

coins. The

digging soon revealed that there were a series of filled fissures on

the hill

crest and soon flint artefacts were being discovered. The first record

shows

“ten well worked flint flakes and two cores”. Building progressed and

Hartley

duly moved in and July 2010 his notes show trays of 2,300 fragments of

flints.

The finds were noted in 1911 to be of Palaeolithic origin but work done

by

Eliot Curwen, local archaeologist catalogued them as a Mesolithic

aboriginies

dagger factory and another member of the Curwen family Cecil went on

record

agreeing with this statement in 1954.

The sad history of the finds is that

they were donated in 1939 to the Museum of Archaeology in Lewes by

Harley’s

daughter and subsequently, as according to Curwen, they were of little

import

or value most of the collection was dumped down a well. The collection

now

consists of 199 pieces of flint and as there are 19 pairs of break

refits this

makes a total of 180 tools.

Starting with Jacobi in 1986 this

collection has now been re evaluated by several experts and pronounced

to be

Early Upper Palaeolithic and of Neanderthal manufacture. At this point

it is

permitted to give a small scream of frustration as the greater part of

one of

the world’s best Neanderthal assemblages was discarded through sheer

ignorance.

Following some geophysical work in the

field next to Beedings house, University College London wished to re

evaluate

the site and a team under the direction of Dr Matt Pope was set up to

excavate

a series of fissures or gulls, their correct title, in undisturbed land

20 feet

away from the house.

The digs that took place for two weeks

in the summers of 2007 and 2008 excavated seven trenches across the

gulls and

other features that showed up on the resistivity. The first task on any

site of

this nature is de turfing, a job not for the feint hearted as this is

thick

downland turf and then the careful troweling could be undertaken.

The gulls are cracks in the greensand

hilltop crest opening slowly as pressures on the Wealden clay below

increased.

In section each gull is a very deep v shape but at the surface anything

up to 4

metres wide. As these gulls formed they were continuously infilled with

silts

and clays and so resemble a knickerbocker glory with its tapering glass

and its

layers of goodies. Each section of layers in the gull represented an

older

period and therefore was really a time capsule waiting for us to dig to

the

correct layer. The top soil and just below contained a mixture of the

last

2,000 years with modern, medieval and Roman pottery as we descended.

The Neanderthal layer was approximately

one metre down in the centre of the gull but shallower nearer the

edges. There

is a natural movement of material the centre of the gull and this

causes

clastic dykes to form in the gull centre formed from larger pieces of

greensand

as they eroded into the gull. The lower greensand is rich in glauconite

that

oxidises and turns a very dark brown from the greenish yellow of the

undisturbed natural.

When excavated the clastic dyke looks

for all the world like a wall running down the centre of the trench and

we had

great fun allowing our site director the privilege of knocking it down

to allow

further excavations. At the time it was commented on that he had

demolished the

only Palaeolithic, Neanderthal, wall in existence but our Director is a

great

chap and took the kidding with great aplomb.

Every piece of flint on the site was

brought in and was either debitage or tools or broken tools. We have a

mixture

of piercers, scrapers, awls, burins and broken blades including one 5

faceted

tip about an inch and a half long. The importance of this discovery

made the

television six a’clock news and is downloadable from the web by

searching

“Beedings” or “lithics at UCL”.

All together a total of 164 finds were

recovered from site and the academic interest was great so we were

visited by

all the top people in Archaeology in the UK and it was a real pleasure

to rub

shoulders with and talk to the real professionals. [editor's note: visit the Beedings

website for more pictures and

information!]

So what did the site tell us about

Neanderthals? Their organisation ability for collective hunting and

planning

was apparent as was the selection of the site showing that hunting was

not just

a hit and miss affair. The finds show a level of technology that was

very

sophisticated compared with their forerunners and collectivisation

ensured a

safer and more stable structure to their society.

I am really pleased that my garden could

have been part of this era and that my bit of land nurtured and

assisted this most

important stage in evolution

Chapter

4 Round Houses

The Devensian ice age was particularly

severe in Northern Europe and the Americas and did not let up until

12,000 BP.

Then followed a brief episode of rapid cooling when it was believed

that the retreating

Laurensian ice sheet changed the course of the melt water flow out

through the

Great Lakes and the Hudson river. This is turn stopped the gulf stream

for a

few centuries so it was not until 11,000 to 10,000 BP that the climate

settled

down to allow Homo Sapien to return to my garden.

The topography at that time was very

different from today with Britain being a peninsular of Europe with no

North

Sea or English Channel. The great rivers of the Seine, the Rhine and

the Thames

all flowed westwards making a very wide barrier so the migration of

peoples was

not from France northwards into England as many texts would tell us but

through

Germany and Holland and then westwards into Southern England.

These new people of the Mesolithic were

still hunter gatherers and the terrain would have been mostly woodland.

Oak,

Elder and a variety of deciduous trees would have covered the landscape

but

here on the South Downs where the soil is shallow large stretches of

open

downland would have made this an idea habitat. Our ancestors would have

had to

compete with bear, wolf, wild pig and some fairly large quadrupeds to

carve

their existence out of this land.

This is the time of the microlith, tiny

detailed flint flakes that made compound tools. The proliferation of

tools was

immense over 120 tool types and a desire for the very best black flint.

The

numbers of people living in this area must have been quite considerable

and

with flint being so prolific the numbers of tools enormous. Every site

in

Sussex and Hampshire that I have been involved in has had prodigious

Mesolithic

blade finds and sporadic bits when walking the dog is common place.

From 6,000 to 8,000 BP the skills were

changing as the transition from hunter gatherer to farmer took place.

The

populous became far more static and the land clearances of trees

started to

make way for a new era that of the Neolithic.

New ideas of living meant new tools and

new usage of flint. Sickles adze, axes burins fabricators all changed

and if

possible even more tools, especially scrapers were used and discarded

into the

landscape to be found later on by me and others.

About 6,000 BC the melt waters of the

glacial stage raised sea levels to such a state that vast tracks of

Doggar land

became lakes and eventually were breached by the rising waters and

formed the

North Sea. This in turn made a massive surge of water down the great

river

channel and formed the English Channel cutting England from France.

During this whole time there was a

gradual change in the way we lived. The flint mines soon gave way to

henge’s, causeway

enclosures, long barrows and of course stone circles. Is there anyone

reading

this that has not heard of Stone Henge, seen the megaliths, wondered at

the

feat of human endeavour. Our landscape is full of hill forts, barrows

and

causeways many of them still very evident today. My garden is about a

mile and

a half from Cissbury one of the major hill forts on the South Downs

(try “Cissbury

Hill Fort” in your search engine or look in Google earth) so I can

totally

believe that this bit of land was hunted on and farmed during these few

millennia.

The South-West end of Cissbury Ring from the air (photo from Sussex

Archaeology website).

The Bronze age followed by the iron age

covered the 1,500 years BC and was a time of settlements and intensive

farming.

The hill tops were still in common use as defensive positions and at

Arundel

and Nore Hill 10 miles west of me there is an area of many square miles

that

was bounded by ditches and covered in lynchetts that gives a fair idea

of just

how many thousands lived in the local community.

Although I have no evidence I imagine my

garden was the site of a round house and banjo enclosure surrounded by

fields

of wheat and barley and a profusion of root and green vegetables. The

house was

24 feet diameter and thatched to keep out the rain and winter storms

and was a

home for mum, dad, children, relatives and in the winter the livestock.

Just up the road is a reconstruction at

Butser so I have a perfect idea of what it was like (click Butser

Iron Age Village to go to official website) the round house was the

centre of living for generations and

was usually surrounded by a bank and ditch with a narrow causeway

entrance thus

giving the name “banjo enclosure”. These enclosures often contained

three or

four round houses and showed that the community was larger than the

extended

family and was possibly the first concepts of village settlement.

Roundhouses at Butser Farm (photo by Bob Wishoff)

One June morning several years ago the

phone rang as I was just sitting down to breakfast. The BBC were

calling to say

that there was to be a television programme in the “Time Team Series”

in the

following month digging on the South Downs about a mile from where I

live and

would I like to assist in the programme. These calls do not happen that

often

when you get on national TV so I graciously condescended to accept (I

am

allowed a few bits of artistic licence in this text). So I was about to

become

a TV personality and with a very quiet Yippeee I casually spread the

news to

everyone I knew.

The programme was to re-investigate a

dig carried out by a local archaeologist by the name of John Pull back

in the early

part of the last century. On the South Downs just north of where I live

is

Harrow Hill, Cissbury Hill and Blackpatch an area covered with

Mesolithic flint

mines. John Pull had excavated several of these flint mines and had

also found

a large circular ditch that apparently had no entrance (try Blackpatch,

Cissbury, John Pull in your search engine)

The programme for Time Team was to

investigate what remained of these earthworks and mines as the area had

been

extensively ploughed in the 1950’s Broadcast in March 2006 (series 13

programme

151) the three days of excavation shown on the television had been

recorded in

the summer of 2005 and in reality took longer than three days.

The area of downland turf had been cut

before our arrival at 8-30 on the Friday morning and we assembled in

the farm

barn for a health and safety talk and a note that there could be

unexploded

munitions in the area as the hill was used during WW2 for the training

of

troops. We were then all issued with a wrist band to denote who was

officially

on site as workers and required feeding. Coffee and hot bacon

sandwiches were

the order of the day and I was feeling that I really could get used to

this

kind of Archaeology.

The walk up to the site was about a

quarter of a mile and we all stood around while the geophysical

research

started several days before was completed. We all watched as the

opening shots for

the TV programme were recorded and panoramic views of the site were

filmed and

the plans of John Pull’s recording were mulled over. By 11-00 we were

all a bit

fed up standing around when it was discovered that the interpretation

of the

original records was wrong and we were several hundred yards too far

south.

This meant getting the farmer and his

grass cutter out again and a further swathe of meadow cut. By this time

it was

lunch and we all trooped back to the yard for a really good BBC meal

cooked in

their massive on site trailer. I must say the food was excellent as I

had now

had two meals and not yet done anything.

By the use of a magnetometer several

sites had been identified and the round ditch, 30 metres diameter

discovered

and we arrived back on site to see a big yellow JCB starting to remove

the

turf. None of this de-turfing by hand on the TV programme, that is

apart from

the little bit done while the cameras were rolling.

The grass was thick downland turf and

below this about 10 to 20 cms of top soil and then a thin layer of sub

soil and

we were on the chalk. It is recorded that a considerable portion of

this part

of the downs was ploughed and bulldozed in the early 50’s to bring more

land

into agricultural use so you can imagine the relief when a part of a

great

circular ditch appeared as a brown stained gully under the blade of the

JCB.

The JCB was digging a blade width trench

across the anomaly so about a metre and

a half was exposed. It was then down to hand trowling to clean the

section and

my job to record the trench thus far. Then the ditch was dug and proved

to be

about 2 metres wide and a metre deep and V shaped. We know that the

John Pull

excavation had revealed the ditch several decades before

but it was soon discovered that the ditch was

not fully revealed, just the infill that left a layer about 10 cms

thick to the

original wall of the ditch so we had a sample for dating.

So ended my first day with a recording

of the section of the ditch exposed. As I was completing the drawing

the JCB

was behind me waiting to get into the trench to expose more of the ring

ready

for diggers the following morning.

Day 2 started bright and early and we

arrived on site to see that over half of the ring ditch had been

exposed so an

army of diggers set to work to expose

the ditch in 2 metre sections with 2 metres between each worked

section. And so

we each had our own small bit to excavate. Before mine was complete I

was

called away by the site Director to record other trenches that a second

JCB had

uncovered looking for small circular features that had been recorded by

the

John Pull dig. It was thought that these were possible round houses or

smaller

circular enclosures but no evidence was found as the land had been

ploughed

away.

What we did find in profusion was tree

throws as this was the time of the land clearances and trees

were

ripped

over

rather

than

being

felled. A tree throw is very distinctive and leaves an imprint of a

crescent

shape almost exactly the shape of a turf edging spade.

On the far side of the slope there had

also been clearances of an area of flint mines and round houses that

had shown

up on the magnetometer survey and two of these had been cleared of turf

showing

the circular row of post holes and the shallow drip ditch. The houses

were cut

into a slight slope so were deeper into the hill side at the back. The

ditches

had to be excavated with care as often there are prenatal burials in

them. On

another site we had found two burials in the same round house and it is

not

known if the children were still born or died at child birth. The one

thing we

were sure was that this was not a sacrificial offering although we have

found

headless chickens buried in foundation before that were sacrificial

offerings.

The flint mine was as we thought just an

in-filled pit so no further work was done as we could have gone down 10

or 12

metres and time did not permit.

By day three the whole site had been

cleared and a large tree throw appeared in the centre of the ring

surrounded by

small pits capped with a flint nodule. In each of the pits was a small

object,

a piece of pottery, a flint tool, and some were stained so obviously

something

biodegradable had been put there. Lots of filming went on and it was

also the

open to the public day so lots of parties turned up to look and comment.

A large pit was discovered next to the

tree throw and this was filled with large flint nodules that had been

mined

from the other side of the hill. So what was this place? Unfortunately

we do

not know but resorted to good old standby of “religious significance”

“ritual activity”

Whatever was happening here no one was

living in this part of the Downs. The pits were obvious token burials

and the

main pit was flint taken from the mines and put back into the ground.

Your

guess is as good as mine.

Although Time Team is supposed to go for

three days on the fourth day I was back helping to record the full

site. Then

the back fill and clearing up just shows you how misleading a TV

programme can

be. This then was the Mesolithic and I can believe that these people

travelled

down the hill a bit and camped and lived in my plot of land. So my

front garden

could have been a ritual site as well so I can add another chapter as

to who

owned this land.

Chapter

5 Here come the Romans

The Month was September the year 55 BC.

Ships seen off the coast at Dover marked the massive change that was

starting

in my garden. Julius Caesar was trying to gain power by extending the

Roman

Empire. The landing at Deal was less than spectacular as he lad been

separated

from all his cavalry but none the less he fought his way off the

beaches and

Britain had been invaded. Over the next two months the Roman invaders

marched

on to the Thames at London had a few battles and then before winter set

in

returned to Gaul. The conquering of Britain was mainly political to get

“Britanicus” as an added name and the setting of taxes as tribute was

instantly

forgotten but the first signs of a new world order were there.

It would take another 98 years before

Claudius brought back the Roman army in 43 AD and by then Britain was a

trading

outpost of Roman Europe and so quite a few tribes, especially along the

south

coast, welcomed the Romans as friends especially the Atrebates, later

to be

called the Regni and their king

Togodumnus. The South coast became immediately a client kingdom and a

magnificent palace was built to show his Roman status (put Fishbourne

Roman

Palace in your search engine). The Roman landings were all along the

South

Coast and as I have a good landing beach in my town of Worthing I can

just see

the Roman infantry being welcomed by the locals and building a marching

camp on

my front lawn.

Part of the geology of Sussex is that

there is a strip of highly fertile soil called brick earth that is

about half a

mile wide that runs parallel to the downs and the sea (referred to in

our

Heidelburgensis dig). This strip was exploited by the Romans and was

settled

with farms along its whole length from Portsmouth to Brighton. Many of

the

farms were tenanted or owned by the local populace and were very

quickly

Romanised. The round house and the enclosure soon gave way to the villa

and

ditches and the Iron Age way of life was no more.

From London northwards the Romans faced

fierce opposition epitomised by Queen Bodicea (pronounced boo-dik-a)

and

several years and several emperors were to come and go until in

Hadrian’s time

England and parts of Scotland and Wales were tamed and under Roman law.

North

of Hadrian’s wall and the Antonine wall there were the barbarians of

Scotland

who were never conquered.

Queen

Bodicea.

So my garden was farmed and settled

until 410 AD by either Romans or Romanised Britain’s and for those four

centuries this was a stable landscape with farms, herds of domesticated

animals

and markets and trading centres. As my garden has very good and fertile

soil I

am sure I was part of an estate in these years and this creates further

images

of who was here and how they lived.

A few miles to the west is a series of

farms in and around the Town of Arundel and its river the Arun. One of

the

farmers, Luke Wishart, a friend of mine, said one day would you like to

look at

my Roman site? And proceeded to tell me that pottery had turned up in

his field

and on a very dry year strange parallel markings had shown up in his

crop. We

walked over to the field that is a sizeable piece of land of 10 or 12

hectares

and waving his hand in a general direction Luke said “in that sort of

area” “It

was a few years ago so I do not remember exactly where”.

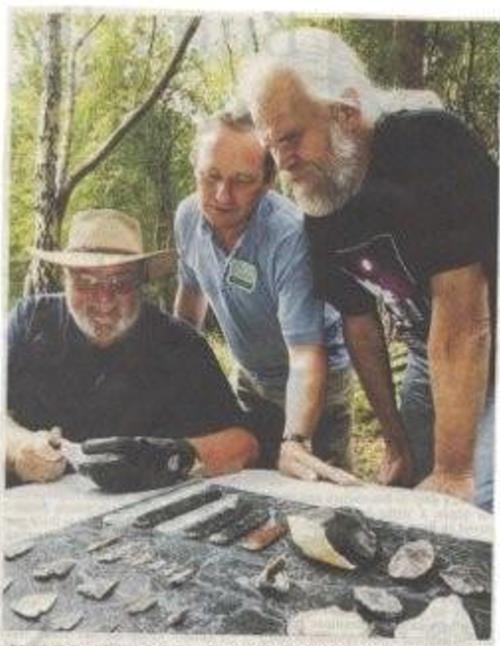

The following weekend several of us,

with the land owners permission, had a general wander over the field

and in the

space of 30 minutes had bags of brick and tile, worked flint, CBM

(ceramic

building material) and about 15 pieces of fineware pottery including

three bits

of Samian pot. Samian for the uninitiated is the Gallo Belgic and Gaul

manufactured high status Roman pottery. If you find Samian it means

very rich

living as only the top rank of the times could have afforded such

luxuries. And

after a few minutes we had three pieces. This was another of those

“wow”

moments.

We all looked at each other but no one

wanted to say much as three bits of pot does not make a villa but the

excitement was there. So these few moments was the start of quite a lot

of

digging as we did not know it then but we had found the missing Roman

Villa.