In order to gain the parameters of the potential site we conducted a “walk over” field survey and then, in a specified area comprising about a eighth of the field, a strip field walk, so we had a pretty good idea of roughly where any settlement could be. Being brick earth the use of resistivity geophysics does not produce a very good result and so we chose an arbitrary base line across our site and started one metre test pits every five metres.

Pit number 1 went down 75 centimetres to

natural and revealed nothing. Pits 2,3,4,5 were all the same-- were we

in the right

place? Were we wasting our time? Pits 6 and 7 produced three bits of

black

burnished ware and a nail then we started to dig pit number 8 this was

an upper

case WOW we hit bang on top of a wall. Flint and mortar starting at 20

cms and

going down a further 80 cms. Our 1 metre test pit soon became a 2 metre

square

trench and then a 4 by 2 as we tracked

the wall. We had a Roman building, and a sizeable one considering the

depth of

foundation!

Test pit 9 at 25 cms produced a floor surface so we knew which side was the outside and which was the inside of the building. The discovery being made we knew exactly where to use geophysics. So, resistivity meters and magnetometers at the ready, we scoured the area. Also, one of our members went over the site with divining rods. Soon we had a feint outline of our building 45 metres north to south and 20 metres east to west. Brick earth is very bad for resistivity (false readings from all of the ireon in the clay) but still we knew roughly what we had so our first trenches could begin.

It’s quite weird to dig into a

structure when

you know quite a lot about the people who made the walls and lived

here. Roman

civilisation remains are very common in this part of the world and just

down

the road is a vast Roman Palace (put Roman Britain into your search

engine) (or

look in Dirt

Brothers Fishbourne Road Trip).

Roman Palace at Fishbourne (photo by Bob Wishoff)

From Tacitus, Pliny and all the great Roman scholars we have detailed accounts of this period and the lives of the people but here I was digging and recording actual walls that they made. In the finds we have samian bowls with the names of the mould makers and the potters so we know “who made me” and in the tiles we have dog paw prints and even a hand and finger prints. In this dig the finds would become very much alive.

Let me side track for a moment and indulge in a bit of imagination because I can see my plot of land being part of a Roman farm. It’s a day at the end of a long hot summer and the crops are about to be harvested. Where I live is wheat and it is destined to make the bread for the winter ahead. It's evening and a long day has meant that the field workers and slaves are just about to set down tools and head back to the farm buildings. The edge of the field is just where my front garden meets the road and a straggly line of workers wind slowly past my home. It suddenly makes where I live very important because I grow things in the same bit of soil and only time separates me from those long forgotten workers.

I am getting too far ahead of myself. Back to the dig. The first year was an extension of the test pits and tracing walls seeing just how big the structure was and trying to get a preliminary view of exactly what we were dealing with. Great interest was coming from the finds as although much of the pottery was simple everyday cooking ware we were also discovering considerable amounts of high status pot including lots of first century Samian.

Then the exciting finds started to come

in, coins, jewellery, broaches / clasps from garments, a bone spoon and

then a

fantastic WOW millefiori glass. To the uninitiated millefiori was the

Roman way

of producing glass before glass blowing was invented where small rods

of glass

were welded together to make the walls of a bowl and then ground into

shape. A

millefiori bowl was an Emperors gift rather than a purchased item, this

was

therefore an exceedingly high status site.

Roman polychrome millifiori dish at the Museum of London

(photo credit: BEN

STANSALL/AFP/Getty

Images)

Digging is only a tiny part of an excavation. There is also recording, photographing, planning, section drawing and then finds processing all of which lasted through the winter months.

Year two saw us back on site this time with far more equipment and far more work to do.

The only way to see what you have in a

villa complex is to expose a considerable area. We therefore borrowed a

digger/backhoe

and exposed an area 40 by 30 metres just removing the top soil-- at

once the

wall lines started showing up. The problem with digging a villa is that

everyone expects one set of walls/foundations thinking the place was

built,

lived in and then pulled down. If only life was like that. From the

pottery we

knew that we had a range of occupation for the site from the first

century to late third century, so our

building was possibly standing for 300 plus years and was modified and

even

rebuilt several times. So as each wall came to light the patterns

and interpretations changed.

Roman well excavated at the Walberton site. (photo courtesy Worthington

Archaeological Society)

Each discovery usually is followed by some sort of guestimate as to what was being found. For example, a wall appears (internal dividing wall OK sounds good), then another wall appears 1.5 metres away (scrap dividing wall we have a staircase…wow…a two story building) then, we expose some of the depth-different build constructions (scrap staircase we now have a rebuild at different dates) and so it goes... each discovery posing more problems than it answers.

The first look suggested five rooms running roughly north-south and with a veranda to the east. To the west there was a tumble of flints, is this evidence of another veranda, or another building, or a wing to the building. Walls in the centre of the complex just tail off : there seems to be a mysterious pit like structure? The southern end has a curved extension have we found a bath house? There is a large burnt area to the south of the building Could this be the stoke-hole (a space in front of a furnace in which a stoker works) for a bath and room heating hypercaust? So ended our second year. By this time all the archaeological Roman Experts had come, looked, pontificated, given advice, argued, suggested, supposed, firmly stated, guessed and generally confused us all.

A strange finds pattern was beginning to

emerge. Just to the north of the end wall of the villa there was a

ditch that

ran parallel to the wall and it was from here that all the first

century finds

were coming. The villa itself was producing 2nd and 3rd

century finds: what we wanted to know was if there was more than one

building. We were all so unsure of what to make of it all -- tentative

ideas were put forward for year three.

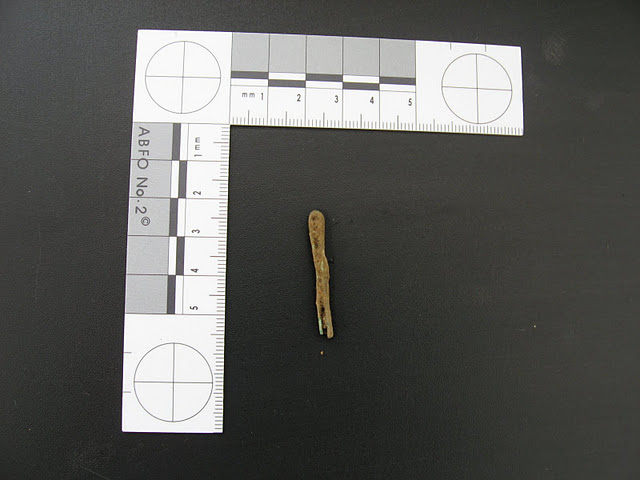

Roman tweezers recovered at the Walberton villa site. (photo courtesy Worthington Archaeological

Society)

However. the farmer was delighted with what was emerging from his wheat field and so we back-filled knowing full well that next year we would gain new insight and possibly new problems.

The following year the idea was to concentrate on a smaller areas and to try and answer some of the questions that the previous year had posed. The large area in the middle of the villa where the walls discontinued was excavated and we discovered that it was a pit dug possibly in the middle ages-- but as there were no dateable finds, it was hard to be decisive. Near the bath house at the southern end of the building we had previously exposed a burned area outside of the villa south wall. This had been assumed to be the stoke hole, but a detailed look at the area showed another burned area on the other side of the bath house. along with another pit and inflow/outflow drain access to the building. The bath house itself was a pair of semicircular apses 4 metres by 5 metres each. side by side

The northern end of the building was showing more walls that supposedly were part of a further room. The sondages (test excavations) in each room established floor levels and the absence of a mosaic floor. During the excavations we found literally thousands of teserae (mosaic pieces), but if these was a floor this had long been ploughed away.

Much of the time during the dig was exploring the area around the villa and an elongated trench to the east produced the print of a round house that must have been on site before the roman Invasion. The ditch to the north was further looked at and although it continued to produce much rich fineware pottery from the 1st century (Samian ware), it added little to the knowledge of the site.

And so to 2009, The plan for this year

was to excavate the northern ditch and the north end of the villa and

take the

apse end of the bath house to foundation level. Some of the villa walls

were

really substantial with mortar flint some 80 centimetres below floor

level, but

when we came to the northern end the walls were nothing like so robust.

The

possibility was that we could have had a two storey building or that

the extra walls at the northern end might be a wooden

tower. The build was not anything as substantial as the remainder of

the

villa and further demonstrated that the various stages of building

spanned several

centuries.

Southeast corner of Roman wall excavated at Walberton

Villa

(photo courtesy Worthington

Archaeological Society)

The northern walls were, to the west undercut by a Bronze Age ditch and we uncovered a further wall that had obviously been erected to support the existing building against encroaching settlement. While excavating this feature all work had to cease as we came across a prenatal burial. All human remains must be reported to the Police as soon as they are found and all work on site cease until the matter is investigated. Soon we had five police officers on site-- a detective inspector, a sergeant, two uniformed constables and a lady police specialist.

In Roman times a child was not named until it was three months old, as infant mortality was so high, so the baby did not become a person until it survived its initial period of life. Our remains were so small that it was thought to be possibly a death at birth. Soon the police were satisfied that the remains were 2,000 years old and not a recent death, so work was soon restarted.

The bones were taken away for further analysis but will be reburied this year with due respect.

A far more detailed plan of the site was now exposed and we have a fair idea of what we are looking at. The first century pottery in the ditch does not seem to fit with our existing building and may indicate that there is yet another building on the site. This will be explored this year in our 2010 excavation as we are extending a very long narrow trench to the east and another to the south east.

Our initial building seems to have been started in the second century and had several rebuilds and modifications being occupied until the late fourth century. At one time the northern end of the building suffered from subsidence and was reinforced and additional room or tower added. The ditch at the north of the building gradually terminates and so our next task is to extend a trench to see if this is the end of the ditch or an entrance to the villa.

So this part of Sussex has come alive for me as the Roman occupation is now very close to me and very understandable and I can see how my garden could easily have been part of this landscape.

There are moments where you can get really close to the people, but they can still surprise you. One day we uncovered a whole chicken skeleton but missing the skull. These remains had been buried next to the wall intact, but headless. Was this a ritual? An offering? A protection for the house warding off evil spirits? We will never know. One thing is clear: the people who touched my bit of land were real, and I would rather have liked to have met them.

We have now finished the dig for 2010

and have further possibly exciting finds. In our second week the

decision was

taken to investigate a seemingly square anomaly that appeared in the

latest

satellite photographs. It is located about 60 metres from the south

east corner of the villa.

Using a resistivity metre was proving useless as the land is brick

earth but a

second sweep at a half metre resolution showed a feint outline that was

investigated with an extended 2 metre trench running south east away

from our

site.

Roman wall and view of excavation at Walberton Villa, 2010.

(photo courtesy Worthington

Archaeological Society)

Immediately we struck a wall but could not investigate for the next three days. There was a low pressure zone coming in from the Atlantic that brought a deluge with it. The site was flooded for two days and any digging resulted in mud up to…., well you work it out.

Brick earth, although non responsive to geophysical surveys, drains rather well so we were soon back on site.

Working from the known to the unknown is always the way in which you progress in archaeology and for the first 20 to 30 metres from the villa we found absolutely nothing. That surprisingly was exactly what we wanted to find.

The “blob” on the geophiz print out was, by the looks of it square, and for those in the know, nothing was said-- the only thing built square in the Roman period was the T word.

Yes, a temple, but no one wanted to hazard this guess, so we all tippy-toed around and waited for evidence to show up. The blank, no finds, area added to evidence as in the Roman culture a temple and its surrounds was the territory of the Gods not to be soiled with earthly debris.

As we dug very fine pottery appeared and then a bone pin used as a ladies hair decoration so was this a temple to Isis? Were the hair pins an offering? Then we recovered a small folded lead sheet. These are defixions and contain either a curse or a blessing. What ours contains we will only know after it has been examined and translated by a conservator. More evidence? Now we only had two days left of our dig time, so two small test pits were dug to try and establish the return wall foundation. A magnetometer was used and appears to show a double anomaly to the north with a gap of about two metres. What was this? But our time was up. The discoveries will have to wait for next year. So watch this space.

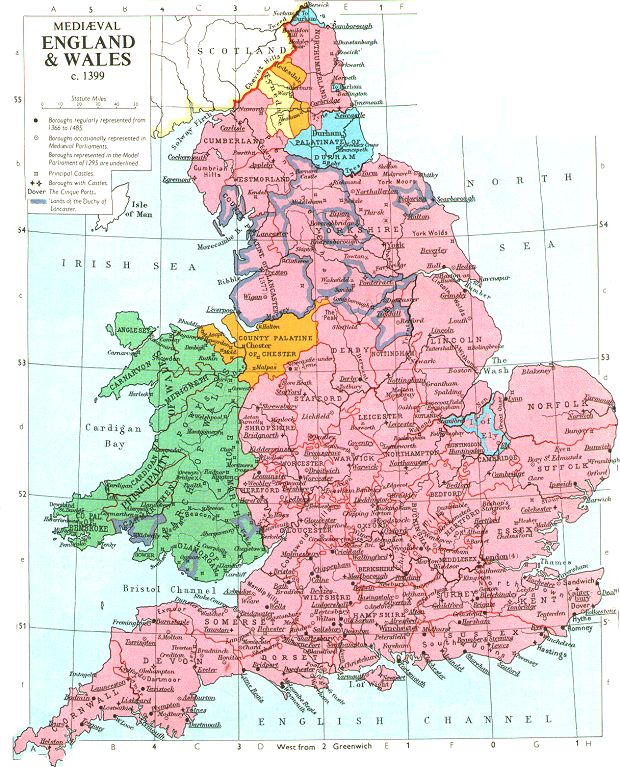

Medieval

England

Map of Medieval England (source)

When the Romans left in 410 AD England slowly descended into the dark ages. The Angles, the Picts, the Vikings and the Saxons have all tramped across my garden and possibly had a pitched battle or two maybe on my front lawn. There is so very little archaeology during these times that I can only conjecture what happened.

By 900AD England was well on its way to becoming unified by the Saxons and written history was returning. Having never been on a Saxon archaeological dig, I have no first hand knowledge of the way people lived. But I can imagine a more uniform, peaceful society based mainly on farming my bit of land.

I can take a further flight of fancy, as this coast was raided by Vikings. A bit of rape and pillage was almost certain to have happened during the 500 years after the Romans, but as very little was ever recorded we just cannot be sure

In 1066 just along the coast to the East the ships of the Normans landed and spilled soldiers up our beaches. Invasion was here again and this land was to have yet again another dramatic series of changes.