|

present Book Reviews For Amateur & Avocational Archaeologists |

|

|

present Book Reviews For Amateur & Avocational Archaeologists |

|

General Archaeology, Flintknapping, Memoirs, Biographies

|

| Home | Gallery | Latest Finds | Back to Main Book Review Index |

|

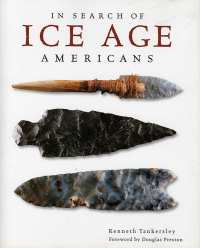

In Search

of Ice Age

Americans by Kenneth Tankersley Foreward by Douglas Preston Gibbs-Smith, Publisher 1991 First ed. 2002 ISBN# 1-58685-021-0 cloth hardback Tankersley enlisted Douglas Preston, a well known novelist, to write the foreward and the entire book's tone flows out from this introduction. Preston makes no secret of his stance that amateurs have found the most important sites in the world, especially the paleolithic world. His expose of the overall topic reads like the novels he writes... just wonderful. Tankersley takes readers on an exciting journey into America's most ancient human past--- from the deep recesses of underground caverns in the East to the mountains and deserts of the West-providing a behind-the-scenes look at the search, discovery, and examination of Ice Age sites and artifacts. You'll find the book hard to put down, from the first "day-in-the-life-of-the ancients" chapter through to the end: Clovis and Beyond. The illustrations are fantastic, with many, many pictures of paleolithic artifacts. You'll really enjoy the chapter entitled "Cowboys and Collectors." Buy this book for a mere $15.72 from Amazon--- click here

to order. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

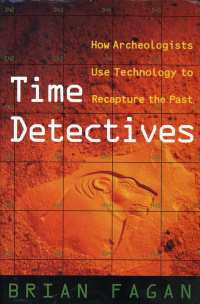

Time

Detectives: How Archeologists Use Technology to Recapture the Past by Brian Fagan Simon & Schuster 1995 ISBN# 0-671-79385-3 cloth hardback Time Detectives reads like a novel. Noting, in the first chapter, the evolution of archaeology from "diggers to time detectives," the author then takes us on a round-the-world jaunt to archaeological sites where technology made the difference in sorting out all of the facts. That is what's interesting about this book--- first, we are shown a set of facts about a site, then shown how prudent use of technology could completely change or expand a site's true story. We are shown the incredible difficulties encountered in some excavations and the lengths professional archaeologists must go to in order to "do it right." At Flag Fen, in the United Kingdom, for example, thousands of bottles of water had to be trucked in to preserve delicate timbers that would have completely disintegrated otherwise. At every turn, professional archaeologists must make decisions based upon real world conditions in the field, and find, many times, situations never before seen, excavation of fragile materials that require the creation of methology on-the-fly, presented with surprise discoveries that require extreme mental stamina to save and study. I think you'll enjoy this book cover-to-cover. Retails for $18.95. Order it from Amazom by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Flintknapping: Making and Ubderstanding Stone Tools by John C. Whittaker University of Texas Press 1999 4th printing ISBN# 0-292-79083-X paperback Wow, what a book! While there are many, many books out there that cover the art and practice of flintknapping, none comes close to illuminating the topic with such depth as this one does. There simply is no element of flintknapping that Whittaker doesn't take on! Written with the avocationalist and professional archaeologist in mind, the book begins with basic principles and history of knapping, and continues with specific techniques, complete with detailed drawings that illustrate each term and technique. Each section contains essential advice for the knapper to follow, guaranteeing the student reasonable results if followed carefully. Tools of flintknapping are also discussed with the pros and cons of materials articulated for knappers at all levels of expertise. The discussion of raw materials will certainly answer a lot of questions as well: the author concisely explains the facts about materials and their composition. Even if you have no interest in knapping itself, the author makes good argument for the archaeologist's interest in the topic. Knowing your flakes, and how they were made can only help a researcher in the field understand what cultures might have been present in an area, and what they were making. It's why professionals count and sort all flakes found at a site. Cutting to the chase, this is simply the best book on the topic that this reviewer has yet seen, and no serious researcher, or avocationalist should be without it in their library! Usually selling for $26.95, order it direct from UT online

and get

the book for only $18.06! Click here

to order this book. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Sandstone

Spine by David Roberts The Mountaineers Books 2006 1st edition ISBN# 1-59485-005-4 cloth/hardcover I took this book to a nicely rugged park near my home and read the whole thing in one sitting. Here's the true adventure of three friends, all experienced climbers, attempting to do something no one else had done before: Backpack the entire 100 mile length of an imposing geological anomaly, Comb Ridge, which runs from deep in Navaho Country northward to Utah. Sandstone Spine is a book about a hike, and perhaps more importantly, a story about three friends who love the land and respect the ancient ones who once lived there. Aside from all of the work that went into caching water supplies and strategizing the route to be taken, we learn a great deal about the trio as they wend their way through their journey. Their spats about which way to go, water supplies, and other ephemeral issues serve to flesh out the book, blend in well with the author's sharp eye for emotional as well as literal detail when they discover new ruins or petroglyph walls. You feel like you know these guys, and it lends to the overall feeling of the book. They meet many isolated Navahos on their trek, and the author never lets you forget when the troupe is on Navaho land. He uses every opportunity to explain the cultural intricacies of the area. The book is a whisk through the known archaeology of the area, with important points repeated occasionaly for emphasis. Perhaps my favorite theme, which occurs throughout the book, is "the outdoor museum", where, despite the fierce competition among the group to find artifacts and ruins, nothing is taken away from the site where it is found. Anything handled is placed back in the exact spot in which it was found. In some cases, they even left notes imploring others to respect the outdoor museum idea: The entire area is a museum of how the ancients lived and should be left alone, preserved until we understand more. The author never really reveals the locations of sites they found. The photographs are fantastic and leave you wanting more of them. This would be a "coffee table" book I would buy! I'd buy this one, too, and I'm keeping an eye out for Robert's In Search Of The Old Ones, another tale of his exploration of Anasazi ruins. Sandstone Spine,

which sells for $24.95, can be ordered direct from the publisher,

The

Mountaineers Books, by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

The New World’s Old

World: Photographic Views of Ancient America Edited by May Castleberry University of New Mexico Press 2003 ISBN#0-8263-2971-3 oversized cloth hardback Photography has profoundly changed the nature of how we think about the past, freezing it in images of light for the future to contemplate. This delightful book arises from a 2003 exhibition held at the AXA Gallery in New York devoted to the role of photography of New World remnants of ancient civilization in changing concepts of the pre-European culture which gave rise to them. Lavish duotones of ancient American ruins, from South America, Central America and the Southwest United States are chosen to illustrate how photography helped shape public perception of the past of the pre-Columbian civilizations that flourished, declined and disappeared on two continents before the European arrival. The accompanying essays provide the thousand words that prove the worth of pictures in these changing views. The editor, May Castleberry, leads off with an introductory overview of the growing understanding of the Americas beyond the early nineteenth century conception of “a place without a past.” Increased public awareness of the magnificent examples of abandoned architecture was enhanced by the emergent availability of photographs lavishly illustrated travel books and magazines such as National Geographic, often contemporaneous with ongoing discoveries, such as Mesa Verde and Machu Picchu. She also explores how the use of cameras as an art medium has broadened cultural conceptions of what these reminders of the past mean to us today. From the earliest days of daguerreotypes photography was utilized as a tool for documenting ancient monuments, a period of which coincided with discoveries of many Central American sites, as well as many different theories of just what these cultures meant and how they arose. Kathleen Stewart Howe, Curator of Prints and Photographs at the University of New Mexico Art Museum, covers the ongoing use of archaeological and commercial photography of ruined Azetec and Mayan monuments in her chapter, Primordial Stones: Reading Ancient Mesoamerica. She summarizes that, “each photographer found something different when he or she framed some scrap of a remote past. Did they see a proud civilization, a past old beyond comprehension, the loss of spiritual communion, or the mystery of human origins?” The second chapter is contributed by Martha Sandweiss, who has published many other works on the history of photography in the American West. The Necessity for Ruins: Photography and Archaeology in the American Southwest opens with a chilling 1869 daguerreotype from the pioneer St Louis photographer Thomas Easterly. It is the last of a series he made over two decades of Big Mound, one of a series of Mississippian culture earthworks that were gradually destroyed as the growing city overtook them, the artifact-filled dirt hauled off as landfill for the North Missouri Railroad. “Like ruins, photographs allude to the passing of time and inevitably evoke a sense of loss…Ruins speak to change and decay…inviting a viewer to strain, from the evidence of what is to speculate about what was, to imagine a decayed structure whole and a part of a vibrant social world.” This speculation, fed by military expedition, railroad and commercial photographers documenting findings in the American Southwest, reached a peak with the discovery of Mesa Verde. The growing availability of cameras opened opportunities for an increasing number of visitors to carry back clear pictures of this most impressive of cliff dwellings and other ancient sites in the newly opened American Southwest to stimulate curiosity about the vanished cultures that gave rise to them. Edward Ranney, a photographer

specializing

in Andean archaeological sites, focuses on the history of photography

of

South American sites in his essay Images of a Sacred Geography,.

Its

scope is broad, including This wonderful hybrid of art book and

archaeological

retrospection is available in oversized hardcover through the

University

of New Mexico Press, here,

for $29.95. reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

Byron

Cummings: Dean

of Southwest

Archaeology by Todd W. Bostwick University of Arizona Press 2006 ISBN#0-8165-2477-7 cloth hardback Archaeology is filled with stories of interesting characters who have devoted their entire lives to the causes of the discipline, but there are few personalities with such a rich and varied career as Byron Cummings. Why have you not heard of this man? Perhaps it was because Cummings wrote for the public and in a language simple and easy to understand: Byron Cummings was not a fan of technical language and jargon and believed strongly in communicating his finds to the public, perhaps even more than to professionals. So Cummings' archaeological work is overshadowed somewhat by his many other talents and his reputation mostly known within the Southwest United States. Here was the consummate "local" archaeologist who fought tooth and nail to keep the then northern academic establishment from running archaeology in the Southwest. Here's a dirt archaeologist who discovered 2 national monuments, including Rainbow Bridge, and explored sites all over the Arizona and Utah area in an era when travel was Tough and took gristle and will. Here's the story of a man who wore many hats: archaeologist, anthropologist, teacher, museum director, university administrator and state parks commissioner. Born in New York in 1860, by 1893 he had made his way to Utah, where while teaching classical languages and literature --- by 1915 he was at the University of Arizona where he developed the State Museum of Arizona which he directed until the 1930's. Under his direction, the museum acquired one of the country's largest anthropology and archaeology collections. This book is filled with interesting stories of Cummings life that will keep you reading and reading till the book is done. I particularly like the chapter entitled "A Good Detective Story, The Silverbell Road Artifact Controversy, 1924-1930." This is a mystery that has yet to be solved, the discovery of "thirty-one lead artifacts and an inscribed stone found deeply buried at an old limekiln near Tuscon. What made these crosses, crescents, batons, swords, and spears so intruiging was their inscriptions and drawings. In addition to Latin phrases and Hebrew words, eigth- and ninth- century dates were also inscribed. Drawings consisted poorly drawn heads, altars, angels, axes, doves, temples, crowns, snakes, menorahs, and other unidentified symbols. Did they show that Europeans had come to America hundreds of years before Columbus?" Cummings soon became embroiled in a major media circus which had all of the great elements of a movie. Oh, if they only could haved proved the authenticity of the artifacts! Ultimately he sort of disowned himself from the controversial Silverbell artifacts that dogged him through the rest of his career (though still believing them authentic.) This is kind of like Tombstone or the Lost Dutchman's Mine," says Don Burgess, guest curator for the Arizona Historical Society's 2002 exhibition of the Silverbell Artifacts. "There are endless theories about the items, and the facts don't change the minds of the people who hold those theories." As recently as this past April 2006, the author of this book, Todd Bostwick, who is also Phoenix city archaeologist gave this talk, “The Bizarre Case of the Silverbell Road Lead Artifacts: One of the Greatest Archaeological Frauds in Arizona History?” at the 47th annual Arizona History Convention. The debate still goes on! All of the chapters dealing with Cummings' discoveries, surveys and excavations will hold your attention. This was a time when discovery still meant travel through rugged, unmapped countryside and Cummings was no slouch, though many could find fault with his less-than-meticulous documentation. He and his lucky students excavated over a hundred sites in his lifetime including Kiet Siel, Tuzigoot, and Kinishba. That's two National Monuments and one National Landmark! In today's archaeological world, with its emphasis on academics, a modern professional can only sigh... it's not likely that they would ever get a chance to be in the field and find one hundred new sites, much less new National Monument and Landmark sites! Those were heady days, indeed! Other chapters illustrate Cummings' talents as teacher and creator of great museums-- he created five. Cummings fought for greater control over archaeological resources. His political efforts changed archaeology in the region, and perhaps set standards for the nation, by guaranteeing local control over regional archaeological resources. Byron Cummings: Dean of Southwest Archaeology is an inspiring read, especially if you are like me and enjoy reading about pioneers of American archaeology. This kind of book keeps me out working in the hot sun, volunteering my time! Order Byron

Cummings:

Dean

of Southwest Archaeology direct from

the publisher for $55.00 by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Trail of Bones

More Cases from the Files of a Forensic Anthropologist by Mary H. Manheim Louisiana University Press 1st printing 2005 ISBN# 0-8071-3104-0 cloth hardback Anthropology is focused study on how people lived, the culture of their lives: it is a discipline which has several major specialties which include Physical Anthropology, the study of the physical and biological factors of primate life. Within this context there is focused study centered around osteology, or the study of bones. Osteological analysis can tell a lot about the life of the primate examined: what they ate, how they lived and died are some examples. So, when anthropologists work with crimes, forensic work, they are called Forensic Anthropologists. Forensic work is one of the hottest fields for an anthropologist to earn a living. Their special knowledge, gained from working in archaeological contexts, makes them especially good at figuring out sequences of events that might have taken place at the scene of a fatality. I have heard that Fox’s “Bones” television show was at least in-part based on Mary Manheim’s career, and after reading this book can certainly see why. Here is a woman who, called in the middle of the night, will trundle down steep railway bridges in search of a missing body part as if it were nothing special, just another outing. Trail of Bones is actually the second volume of stories told by Manheim, the sequel to the successful The Bone Lady: Life as a Forensic Anthropologist (ISBN 01402.9192X (pbk), Penguin Books 2000). There are 15 stories in Trail of Bones, covering the aforementioned railway bridge scene and diverse others which include murder victims found in all sorts of scenarios. Using clues such as tattoos, clothing, and DNA to solve a murder—Manheim explains her methods to us. Life is no television show, and Manheim exposes us to the gritty realities of her work, along with the sometimes bizarre crime scenes and her all-hours-of-the-day work schedule. There are chapters about her work with Bigfoot investigations, the Space Shuttle Columbia tragedy and her help in ascertaining the identity of a slain Korean War soldier. After reading the book, you will understand how a forensic anthropologist uses scientific methodologies to solve a murder, even a very cold case. Manheim is a great story teller, writing in a straightforward style, she whisks us through the cases, never talking down to the audience, explaining complex issues with well thought out understandable prose, remarkably free of jargon. I enjoyed this book, and will likely

read her

previous volume as well. It’s a great summer read! You can order Trail

of Bones directly from the publisher for $24.95 by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Paleoamerican

Origins: Beyond

Clovis Edited by Robson Bonnichsen, Bradley T. Lepper, Dennis Stanford, and Michael R. Waters Center for the Study of the First Americans 2005 1st ed cloth hardback There’s not many books I’ve been more eager to receive than this volume, dated 2005, but only recently available, perhaps due to problems encountered by the untimely death of CSFA founder, Robson Bonnichsen. The Center for the Study of the First Americans poses the following questions on their website: When did the first people enter the Americas?; Who were the first immigrants?; Where did they come from? And finally, How did they get here? In 1999, in an attempt to answer those questions, the CSFA sponsored a conference called “Clovis and Beyond” from which many of the papers in this book were originally presented. What Paleoamerican Origins seeks to do is to provide a platform for the rethinking, indeed the rejection of, the Clovis-first model of how the “New World” was populated, supposedly by migrating hunters across the Siberian Peninsula. “According to the tenets of the Clovis-first model, these hunters, armed with a new and supposedly more efficient killing technology--- most particularly, the Clovis projectile point--- brought about the rapid demise of over 33 genera of large game animals in North America and 55 genera in South America in under 1,000 years.” “In our view, the long standing impasse between the Clovis and pre-Clovis camps has been broken. With revelations brought about through the discovery of new archaeological sites older than 11,500 RCYBP [Radio Carbon Years Before Present] and integration of new skeletal and genetic evidence, many specialists have rejected the Clovis-first model.” What this book does is cover its topic inside and out, making convincing arguments for increased attention toward research which seems to contradict established models for the occupation of this continent. What’s amazing about this book is that the reader is exposed to so much research that has been shoved under the rug, ignored by the “establishment” because it did not fit into that Clovis-first model! Whether it be North American sites like Meadowcroft Shelter in Pennsylvania, and Topper in North Carolina, or Kenniwick in Washington, or at sites across South America, there are research summaries that seem to debunk the notion that humans were not present on the American continent before Clovis. Could we have been looking in the wrong places all this time? Did archaeologists stop digging too soon? Were assumptions made about some data, relegating “what didn’t fit” to the status of anomalous, contaminated or irrelevant? It’s all part of one of the greatest mysteries in history and everyone’s got an opinion, a passionate opinion at that. There is debate at every level of every facet of this research. It is plain, as many of the papers make clear, that a new set of standards must be established, as well as definitions re-worked. For instance, with pre-Clovis ages added in, the standard Paleolithic chronology no longer makes as much sense and so there are at least two site’s/area’s chronologies put forth and discussed. Just how far back one should define an age isn’t is as simple a decision as it would seem. Unbelievably, in Mexico, there are some tantalizing bits of data that indicate occupation ages at sites that could be 40 to 80,000 years old! Research and hard data are going to be needed to compile a set of models that can generally be agreed upon. Paleoamerican Origins, states its position and with paper after paper duly presents that hard evidence and challenges its readers to open their minds. The “Conclusions” section of the book examines today’s research environment with its new technological advancements in analyses of DNA, AMS Radiocarbon dating, etc. contrasting with increasing pressure from laymen critics who would limit research for philosophical reasons. This pressure has made research difficult, especially when it come to burial remains. “Alongside these advances, however, have come other developments that are not as positive for the future of First Americans research. Science and its explanations for understanding the world are being challenged by critics who advocate non-empirical ways of explaining empirical phenomena… If the critics of science have their way, future advances in understanding the peopling the Americas will come to depend more on political considerations than on hard work and scientific critiques.” What follows is a thorough discussion of the history of repatriation issues, especially the effects of NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990) on First Americans Research. This is controversial material, for sure, and you will no doubt already have an opinion. The authors are clearly not happy with what they consider to be flawed Tribal claims: “Despite their scientific importance, however, some of the oldest and best-preserved remains have been transferred to the possession of native tribal claimants who have no known affiliation to the remains in question. In each case, the remains were buried in a location known only to the participating tribes. Depending on future political and legal developments, many of the remains that are still left in federal and state collections could suffer the same fate.” Is “knowledge” a shared cultural heritage, or does it “belong” to one or another social group? This section is packed with information about funding agencies and archaeological societies, their positions clearly laid out for you to ponder. Is the research effort in need of a strong leader who will lobby for it? “First American studies are something of an orphan in the world of scientific organizations… More effective leadership on the part of the professional scientific associations is essential if First American researchers hope to withstand the ongoing challenges that are being raised to the legitimacy and value of their work.” There is lots of provocative thinking going on here which will be the basis for much conversation by interested readers and their comrades. Finally, the book concludes with a paper entitled “Paleoamerican Origins: Models, Evidence and Future Directions.” This is perhaps the best publication in the book in that, after all the material in the rest of the book has been read, this publication successfully summarizes it all, and put together in one report, the new evidence has a solid coherence, a platform for the future research it suggests. Paleoamerican Origins: Beyond Clovis

is one of the most though-provoking books I’ve read in a long time and

should be read by anyone interested in archaeology, anthropology or

history.

Order it direct from the Texas A&M University Press Consortium, for

$60.00, by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Indian Country:

Travel in the American Southwest, 1840-1935 by Martin Padget University of New Mexico Press 2004 ISBN# 0-8263-3028-2 paperback During a 1990 trip to the Taos Pueblo, Martin Padget found that paying a $5 entrance fee and $5 camera fee left him with a vague sense of unease. “(T)he issue at stake was not a reluctance on my part to provide Taos Indians with much-needed revenue but that the grounds of exchange between myself, a tourist, and the people I was visiting had been predetermined. Walking around the pueblo that day, I grew fascinated by the actions of fellow tourists…To what extent did tourists’ photography crystallize an urge to consume and appropriate the culture of Taos Pueblo and to what extent did it express an earnest wish to learn more about Native American cultures? How did Taos residents view their visitors, and did they differentiate between the ranks of tourists?” The evolution of this interplay between the interests of `visitors in the American Southwest and the native cultures they vicariously participate in form the basis of Indian Country. This often uneasy relationship between native cultures is explored through accounts of early travelers in the Southwest and the influence they exerted on public perceptions its native populations. Padget investigates how a growing tourist industry seeking an “Indian experience” ultimately shaped the relationship between the two cultures. He draws on a wide variety of artistic and written portrayals to demonstrate how what was seen as a vanishing way of life was merely a transformation of the interactions between two ways of life to accommodate a shifting power differential. Ultimately the perception that an exotic way of life could be gratuitously shared merely by traveling west to Indian Country helped lead to preservation of traditional ways of life at threat of extinction through assimilation. The military exploration parties John Fremont, James Simpson and Zebulon Pike by their very nature hinted at the appropriation of lands and peoples to come at the hands of Manifest Destiny, while books by Midwestern traders suggested a growing awareness of the commercial potential of the Southwest as a travel destination. John Wesley Powell, while most famous for his scientific and ethnographic explorations of the Colorado Plateau, also popularized an exotic view of Indian rites and rituals in his Canyons of the Colorado and a series of widely read articles for Scribner’s Monthly; he also initiated a growing trend of Anglo intrusion into kiva ceremonies despite objections by many of the Indians involved. The literature associated with the nostalgic appeal of life among the California missions and Indian tribes played a significant role in the later part of Richard Henry Dana’s famous 1840 novel Two Years Before the Mast, but Padget devotes the better part of a lengthy chapter to the results of Helen Hunt Jackson’s now mostly forgotten novel Ramona . Published in 1884, this tale of a half breed’s ill fated romance played an important role in the marketing of southern California as an idyllic escape from the hectic lifestyle of the late nineteenth century to an idealized slower pace of life in the West. It sparked a spate of articles and books espousing sympathy with the plight native tribes and mission life that were being extinguished in the oncoming wave of Euro-American settlers it ironically helped foster. The works of Charles Lummis, who literally walked to California across the Southwest in 1884-1885, brought his view of Spanish and Pueblo culture to readers in books such as Some Strange Corners of Our Country and The Land of Poco Tiempo. Art also played a role in establishing the public’s exotic view of the Indian Southwest, and a chapter on the sadly enigmatic artist Elbridge Burbank presents a portrait of an artist who found solace amongst the Indians he lived with and painted under commission to millionaires; unable to cope with the pressures of the life he’d left behind he spent the end of his life in California asylums and peddling copies of his work to survive. Padget finishes with a look at the development of the Indian Southwest as a travel destination by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. The vast influx of tourists, who eventually outnumbered the indigenous participants at ritual such as the Snake and Antelope Dances, eventually fostered changes in the willingness of Hopi, Zuni and other tribes to accommodate those tourists, shaping the uneasy environment which Padget encountered in Taos in 1990 and still overshadows the experience of even casual visitors to the Southwest today. Although at times tending towards academic literary deconstruction, Indian Country remains eminently readable, prompting the reader to consider a deeper reading of other early accounts of Indian culture for insight on how they shape contemporary viewpoints. Indian Country

can be ordered directly from the publisher by clcking here.

reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

James A. Ford and

the Growth

of Americanist Archaeology by Michael J. O’Brien and R. Lee Lyman University of Missouri Press 1998 1st ed. ISBN# 0-8262-1184-4 cloth hardback There is a great deal of theory surrounding archaeological activities, theories which took great debate and much research to formulate. In fact, there have been several “revolutions” of thought surrounding concepts the very nature of what archaeologists are meant to really be studying. Chronologies, ideas about cultural “evolution”, theories which developed into typologies, all are still subjects of discussion amongst professionals. “For much of the twentieth century, culture history was the major paradigm of Americanist archaeology. It finally fell from favor-- at least in name – in the face of increasing challenges that it was theoretically vacuous and concerned solely with the chronological ordering of artifacts… This assessment was correct, though it is clear that most culture historians decidedly had the explication of cultural development as their ultimate goal. They ultimately failed on methodological grounds, not for want of purpose… Through their development of chronological methods, culture historians provided archaeology with a sound footing in science, but because of their interest in artifacts as cultural phenomena, they were faced with a paradox: how could the units formulated to measure time be used simultaneously to monitor culture change? Nowhere is the constant tug between the two interests more apparent than in the work of James A. Ford… Ford’s work demonstrates that the root of the paradox lay in the fundamental differences between two competing ontological perspectives—essentialism and materialism. No amount of tinkering could enjoin the differences; ultimately, this led to culture history’s fall from grace and to its replacement by cultural processualism.” In other words, culture historians believed that only timelines, or chronologies could be gained from the archaeological record, that cultural processes (how people lived and interacted, their lifeways) were lost forever. Cultural processualism, on the other hand, adheres to the ideas of cultural evolution whereby artifacts are evolved out of cultural necessity, taking the place of biological evolutionary processes and that, therefore, artifact analysis can tell us a great deal about the culture which made them. Ford’s work, as presented by the authors, demonstrates how the early Americanist archaeologist found himself at the center of this controversy. A prolific researcher across the southeast US, Ford’s papers highlight his own struggle to create chronologies of pottery typologies and how the essentialist/materialist paradox got in the way of the task. That Ford’s goals were ultimately to gain control of the chronology of the archaeological record, an important aspect of any study, and that he had an interest in studying culture, seems to have been lost in unfair criticism of his work. The authors’ intent with this book is twofold, to investigate and highlight the basic evolution of conventional archaeological theories and to show Ford’s important role in this process through his research and publications. What we readers are given is an examination of theory and a unique kind of biography. Ford was a colorful personality, one who would not suffer fools, “A fairly quiet, at time brooding man, but one with a large ego, Ford pushed through and executed a plan of attack regardless of the consequences. He apparently didn’t much care whose toes he stepped on, especially if they belonged to someone less adept than he.” When the New Archaeology of the late 1950’s began to arise, critics began to lambaste Ford’s ideas without really critically examining his work, thus Ford’s work has not been fully appreciated. That the world may have forgotten this important archaeologist seems a shame to the authors, and after reading the book, you might agree with them. A reader of this book will also come away with a better understanding of past and current thinking about what archaeologists do as well as the true nature and value of their field data. Without theory, there is little value to artifactual material analyses. James A. Ford and the Growth of

Americanist

Archaeology can be ordered direct from the

publisher, for $49.95, by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Journeys to the Edge:

In the Footsteps of an Anthropologist by Peter. M. Gardner University of Missouri Press 2006 1st ed. ISBN# 978-0-8262-1634-2 paperback On one level this book can be read as an anthropologist’s investigation of the native Dene tribes of the Canadian Northwest and the primitive Paliyan tribes of southern India, with a later side trip through modern Japan. On a much more interesting level this is the story of the author’s discovery on a deeper level of what it means to be a human amongst humans, trying to understand humanity. This may sound a bit much, yet it makes for one of the most enjoyable accounts available of contemporary anthropology. As the Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of Missouri-Columbia, Peter Gardner is fully capable of producing a more academically rigorous account of his research, and indeed he has. His skills as a writer, however, find a more relaxed outlet in this autobiographical account of his travels with his family in remote regions of the world. Incidents that might have no place in professional publications, such as life threatening illness, hunting expeditions with the sons of rajahs to isolated Hindu temples, or finding oneself in the depth of an Arctic winter’s night with a snowmobile that won’t start ten miles from the nearest community, do make for much more interesting reading though. One comes to feel close to his family, happy for their adventures in wild, exotic locations, anxiety as they fall sick in a third world country, and oddly sad when it becomes clear that his first marriage has fallen apart. And his growing Taoist sensibilities that emerge amidst an ongoing bout with cancer in his later years lend an air all-encompassing spirituality to his adventures that is free of any sense of cloying religiosity. But there is plenty of anthropological meat to chew on here too. His work with the isolated hill tribes of the Paliyan is surprising not only because of their remoteness in the midst of the densely populated subcontinent of India, but also because of the degree to which as a hunter-gatherer society they embrace a life that successfully shuns conflict. His work while living with the sub-Arctic Dene peoples opens insights into the private worlds we all share in public, with his confirmation of how individuals even within their small community “…varied from one another considerably in their terms, their concepts, and even their broad frameworks for thinking about familiar things.” Even his accounts of an academic sabbatical in Japan and receiving treatment for a metastasizing cancer become a meditation on the subtle differences in approaching problems that persist beneath modern cultures. There is a persistent tone of hopefulness and joy in Gardner’s work that pervades this book, making it a pleasantly surprising scientific autobiography while at the same time illuminating the inner workings of modern anthropology. Illustrated with photographs by the author and maps of his areas of work, it’s available from the University of Missouri Press (here) for $19.95. reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

Adela

Breton: A Victorian Artist Amid Mexico’s Ruins by Mary F. McVicker One of the major figures in Mesoamerican archaeological circles in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century is now almost completely forgotten. Adela Breton began as an amateur with no academic background in the fledgling sciences of anthropology or archaeology, but her diligent efforts in depicting ruins and especially newly uncovered Mayan frescoes soon made her work invaluable to the academics of her time. As Mary McVicker points out in the first chapter of this book, “The late 1800s was the glorious age of the amateur, before entry to professions became more credentialed or, some might say, more calcified. Women were making small inroads into professional ranks, albeit slowly. Adela used her work to carve out an identity for herself within a scientific profession. If she ever aspired to the institutional and male-dominated inner circles, she gave no indication of it. Instead, the impression she gives is quite the reverse, that she rather enjoyed being professionally in demand yet outside the politics and bureaucracy and not tied to an institution with its potential for limiting her range of work.” Her most

outstanding work was

done at Chichen Itza,

which at that time was located on a hacienda owned by the American

consul to Yucatan, an ambitious

anthropologist by the name of Edward H. Thompson. Thompson’s

relationship with the Mexican

authorities was precarious due to his propensity for smuggling works

out of the

country in violation of their antiquities laws, and he exercised a

proprietary

interest over the work being done there.

His relationship with Adela was prickly at best, and from their

existing

letters it is clear that this feeling was mutual; most of her time

there she

chose to live with Pablo inside the ruins themselves, rather that at

Thompson’s

hacienda, as did most other visitors to the site. Adela’s most

outstanding work was done there,

capturing in vivid tones and hues the remnants of the once extensive

murals in

the Temple of

the Jaguars. reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

Pot Luck:

Adventures in Archaeology Florence Lister is one of the grand old ladies in Southwestern American archaeology, and it is a real gift that she is also so wonderfully eloquent in writing about it. In reviewing Lister’s Behind Painted Walls: Incidents in Southwestern Archaeology for American Antiquities, Lynn Sebastian has compared her books to “sitting at your grandmother’s kitchen table listening to your aunts and uncles tell stories about the adventures and antics of beloved (and not so beloved) family members who are now gone.” While Pot Luck is an autobiography, her beloved late husband and love of the study of ceramics certainly play an important role in the telling of her story. Books on archaeology by wives of archaeologists have held a special interest for me since first reading Digging in the Southwest. Written by Ann Axtel Morris, first wife of the legendary Earl Morris, it is witty, insightful and full of delightful anecdotes. It provides a slightly removed view into the cycles of excitement and drudgery encountered while excavating in out the way locales, a vantage point that a wife living side by side with her husband is especially equipped to provide. It not only provides an intimate view into the exciting early days of Southwestern archaeology, it is also a joy to read with it’s lightness of tone, lack of pontification and hilarious asides. It was a pleasant surprise to find that prior to her marriage, Florence Lister had also come across this jewel, “which, from a wife’s perspective, recounted field work in an untamed sector of the Southwest that offered adventures, intellectual challenge and downright fun. More than I knew at the time, that book was to have a profound influence on me because I identified with what I saw as an exotic life played out in a supporting role.” At the field school in Chaco Canyon where she met her husband, Lister also found an outlet for the love of ceramics she’d first encountered in a Los Angeles museum where she first viewed an Anasazi corrugated pot still embedded with it’s maker’s fingerprints. She soon found herself relegated to the exacting and tedious chore of sorting and classifying potsherds, a task at the time was often considered more of a woman’s role but which she found to be a labor of love. Her academic career was soon put on hold by the demands of raising of their two small children, but she still managed to become an invaluable expert on her husband’s archaeological expeditions and a much sought after specialist in her chosen field. But Lister hardly takes a supporting role in this book; her better known husband is always present but it is her passion for pottery and ceramics analysis that comes to the fore. The result is a charming autobiography which reveals as much about the results of her research as it does about the worldwide adventures of her personal and professional life. We follow her and her husband on archaeological adventures at Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Glen Canyon and other sites throughout the Southwest, working side by site with such eminent archaeological figures as Earl Morris, Florence Hawley, Jesse Jennings, Edgar Hewett and Anna Shepard. They visit sites throughout Mexico, Central America (where her family finds themselves trapped in the lightless tomb of the great Mayan pyramid in Palenque), South America and the Caribbean (where they were attacked and robbed in Kingston). She and her husband’s work found them sought out to do salvage archaeology for the Aswan High Dam project on the Nile, and we find her tracing the significance of the Moorish influence on pottery throughout Morocco. She traces the lines of maiolica pottery found in old Spanish sites in America to the discard piles of ancient kilns in Granada, and the dissemination of porcelain expertise throughout the Far East while teaching traveling students on a shipboard college touring around the world. This is no dry exposition of her work, and her presentation of the facts lead the reader gently leads the reader to share her excitement about the evolution and technology of pottery and ceramics throughout the human experience. Anyone with even a passing interest in the subject will find their curiosity sparked to learn more, while specialists in the field will find a kindred spirit who has done much to widen our understanding of the subject. But this book is about much more than her love of pots. Her love for husband and the life they shared together is also manifestly evident throughout the book; it is clear that this was a wonderfully blessed marriage of minds as well as of souls. She devotes the concluding chapter to summarizing the life of her husband Bob, a life steeped in the rich heritage of the southwest. Raised on a historic ranch on the Santa Fe Trail, participating in momentous archaeological projects and becoming one of the leading figures in our understanding of the prehistoric Southwest, he died with his boots on there, climbing a trail out of Grand Gulch after visiting a cliff dwelling there. This is just one of a number of thoroughly enjoyable books by Florence Lister from the University of New Mexico Press. Pot Luck can be purchased from their website for the book here for only $19.95. You’ll find yourself looking forward to reading more of her work not only for its archaeological insights but for the sheer joy of her skills as an author.reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

Travels and

Researches in Native North America, 1882-1883

With these words, Dutch anthropologist Herman ten Kate summarized the guiding principle behind his one man journey to the United States and northern Mexico in 1882-1883. Over the next 13 months he studied and lived among a surprisingly large number of Native American tribes, collecting information on their culture, language and religious practice. He also quantified the skin coloration, stature and cranial capacity of as many Indians as he could, a source of hesitant amusement for many of them. His determination to acquire museum specimens for his sponsors led him to purchase items of daily use, while a phrenological bent to his studies led him to obtain as many skulls as he could obtain by either hook or crook, a practice sure to send shudder down the spines of latter day anthropologists. Returning to the United States in April of 1883, ten Kate then spent time with the Apaches, Mohaves, Paiutes, Pimas, Walapai and Chemehuevis in Arizona, as well as surveying the ruins at Casa Grandes and other archaeological sites. He then spent most of his summer among the Navajo, Hopi and Zuni, living among them in various pueblos, witnessing the Snake Dance at Walpi and staying for a time with the eminent ethnologist Frank Cushing, who became a lifelong friend. From there he traveled east to the Ute and Cheyenne reservations, on to Indian Territory to study the Comanche, Kowa, Witchita, Caddo, Choctaw, Creek and Cherokee tribes before returning to the Netherlands in December of 1883. Nineteenth century travel narratives play an important role in our understanding of the changes Native American cultures faced as the United States began its inexorable expansion westward. This previously un-translated account of ten Kate’s amazing journey lends a particularly interesting view of the changing world of the Indian in the American West. He is ever cognizant of the pressures on them to abandon their previous cultures and conform to nineteenth century civilization, while his view is devoid of the onerous mentality of Manifest Destiny that weights down so many of his contemporaries. With the insight that an outsider has particular access to, he views with open eyes the phenomena of a frontier where a native population is being rounded onto reservations where its cultural background is faced with assimilation or destruction. Here one finds a chance to see the Southwest of the early 1880s with fresh eyes. His observations are wide ranging, covering topics such as detailed descriptions of the physiological characteristics peculiar to various tribes (including proportional incidences of albinism), sexual practices and mores (in Latin), living quarters, modes of subsistence, hairstyles, burial practices, and any other details he could glean during his stays with them. He includes detailed descriptions of the local landscape, climate, weather, flora, and fauna, while the coarse peculiarities of the white inhabitants of this New World fall prey to his Old World sensitivities as well. Ten Kate’s

report on his travels offers an eloquently stated

view of this vanished period of time in America and its aboriginal

peoples on

the brink of extinction. Previously

available only in the Dutch language, Travels and

Researches in Native North

America is now available from the University

of New Mexico Press’s website

(hardcover, 8x10, $60). Although

unfortunately his attempts at photography did not survive his travels,

the book

is illustrated with the small number of representative photographs and

halftones of the tribes he visited, as well as of ten Kate himself.

Though it lacks a map to trace his progress

studying a native population he felt was rapidly approaching

extinction, it

remains an impressive guide to his little known journey. reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

Dirt:

The Erosion of

Civilizations Author David Montgomery wastes no time getting to the point of his book, writing early on in the first chapter, entitled “Good Old Dirt”: “We try to keep it out of sight, out of mind, and outside. We spit on it, denigrate it, and kick it off our shoes. But in the end, what’s more important? Everything comes from it, and everything returns to it. If that doesn’t earn dirt a little respect, consider how profoundly soil fertility and soil erosion shaped the course of history.” Mongomery, professor of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington, writes in an easy-to-follow, breezy style — he’s quite good. I found myself taking this book along on errands, filling in chunks of time with each chapter as I might a novel. In order to truly appreciate dirt, “the skin of the earth”, one must appreciate just how long a time it takes for even a one inch depth of soil to accumulate and become arable. Interestingly, it was Charles Darwin who, in one of his last books, “The Formation of Vegetable Mold, Through the Action of Worms” published in 1881, who Montgomery credits with “discovering something fundamental about our world…Darwin’s worm book explores how the ground beneath our feet cycles through the bodies of worms and how worms shaped the English countryside.” I absolutely enjoyed reading Montgomery’s skillful blending of Darwin’s work into a broader picture of geomorphology: How many authors can do that? What is created surely erodes away, and erosion rates are difficult to predict, even after over 50 years of study. Introducing the history of farming and the delicate relationship between river deposits and over-farming, it becomes obvious to see where this book is going. Montgomery examines the births and deaths of classic civilizations and points to conditions of the soil as major reasons for their collapse. He examines the politics of colonialism and shows how colonial empires raped the soil of their colonies. Not caring what the long-term effects might be, they harvested crops which deprived the soil of nutrients and deforested areas which promoted chronic erosion. Somehow Montgomery combines geomorphology, geology, archaeology and world historical perspective into a compelling tale of yet another resource we have all taken for granted. This is an important book which you will enjoy reading! Dirt

can be ordered directly from the publisher by clicking here,

for $24.95 (cloth hardback). reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Native

North American Armor, Shields and Fortifications

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Geoarchaeology

in

the Great Plains reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

SPECIAL FOCUS

BOOK REVIEWS--- KENNEWICK

MAN

There

continues to be incredible interest in the Kennewick Man discovery.

Here are a few of the best books on that topic and its wider

implications. You might also want to read Robson Bonnichen et al.'s Paleoamerican Origins, a review of

which can be found here. All

reviews written by Bob

Wishoff.

Bones: Discovering the First Americans by Elaine Dewar Carroll and Graf 2004 paperback ISBN# 978-0-7867-1377-6 This massive 628 page book is a fantastic read! I could not put it down. After I read it, I lent it to a professor, who also could not put it down. What Dewar has written is a fast-paced investigation which takes the reader on a continent-wide hunt for the first immigrants to the so-called "New World." Dewar finds a science, physical anthropology, beset by politics and pre-conceived ideas. She finds scientists who insulate themselves from the "bigger picture" by their profound unwillingness to investigate claims made by scientists from other disciplines outside of their usual frame of reference. She's speaking of sciuentists who won't budge outside of status-quo perspectives--- those who would ignore hard evidence that would seem to debunk their own "pet" theories. One example of this lay within the general attitude by scientists toward work and evidence gatherered in Brazil. Researchers there have found anomolous bones and rock art that purportedly show a much more ancient presence of humans on this continent than previously thought. These remains, if valid, would show that humans needed more time to move down through the Americas than would be possible given current thinking about the land-bridge from Siberia as the main corridor for immigration. But, Dewar maintains that English-speaking researchers seldom even read journals that are not in English, and therefore, much data are ignored by the larger mass of researchers. Interestingly, Dewar spotlights new research that shows that the main corridor thought to have allowed for migration into the continent did not even exist during the time period previosly believed, thus pushing possible immigration later than earlier reported! Where are the ancient remains, she asks, that would add evidence to theories of migration that have been taught to children for a generation?? Dewar's book is an excellent starting place for anyone interested in this topic. She takes the time to give the reader a full background in the problems and techniques of physical anthropology. She outlines the political pitfalls of working with ancient remains. She interviews all of the major players, and like a good journalist, provides the reader with thoughtful in sight into how science works in the real world. Focusing on legal cases surrounding skeletal remains, especially the famous Kennewick Man remains, Dewar concludes that the current pactitioners of physical anthropology are "fractious and litigious... hampered in their outlook by their acceptance of authority, by national boundaries, by possessiveness about finds, by conservative gatekeepers who control the flow of research money, by their fear of stepping one inch beyond their expertise onto someone else's turf, and by the organized outreach of Native Americans." In addition, she writes, that the increased specialization required by new technologies (genetic, for example) make researchers less able to read and interpret each others work-- and therefore limits their ability to make use of important data. Bones is a wonderfully engaging book that you will pass around to your friends-- here's a platform for many, many interesting discussions. If you are interested in the first residents of the Americas-- it will give you a broad understanding of the topic that will help you understand the viewpoints expressed in other books on the topic. Bones is a best selling book, widely available at book selling chain stores, and sells for $16.00. Ancient Encounters: Kennewick Man and the First Americans by James C. Chatters Simon and Schuster 2002 paperback ISBN# 978-0-6848-5937-8 In 1996, forensic anthropologist James Chatters was presented with a skull thought to be a victim of homicide-- what followed was not what he expected at all-- Chatters would soon be at the center of a raging controversy that would gain him international attention and change his life forever. Initially, this looked like a pretty straightforward case. Chatters' first look at the skull convinced him that he had the bones of a Caucasian male. Upon examining the remains in order to ascertain cause-of-death, researchers found a flint dart point embedded in it: this single Cascade projectile was last used by humans nearly 10,000 years ago. Astonished by this, Chatters ordered radiocarbon tests to be done on the remains and these tests showed them to be over 9000 years old! How could this be? Chatters inquiry opened up a can of worms-- Native American groups in the area were soon actively arguing for the cessation of all testing on the remains. They wanted them back, and they wanted them immediately. Who would argue the case for science, asks Chatters? Are the bones the property and responsibility of the Army (which owns the land it was found on), or should the remains be assumed to be related to local Native tribes, despite little resemblance of the skull to others found in the region, or to modern Native Americans? Ancient Encounters gives the reader an up-front, insider's look at the politics of modern-day physical anthropology. Chatters recounts his side of the entire Kennewick affair. We read of his phone conversations with everyone who got sucked into the fracas between scientists, Natives, and the Army. Chatters found himself at the center of a whirlwind controversy, especially after the release of a forensic reproduction of the Kennewick man's supposed image, one that stunningly looked like Star Trek captain (and Frenchman) "Jon Luc Piccard." Careers were put into jeopardy. Long time relationships between Native Americans and professional anthropologists and archaeologists were fractured. The Army hastily buried the site where Kennewick Man was found under tons of cement. Accusations about attempts to hide the bones away, were lashed about, and the law called into play. Chatters and his colleague were subjected to an investigation by the FBI. The author paints his inquiry into the identity of the Kennwick Man remains as an honest one, and seems "gob-smacked" that this would have made him the main target of Indian anger. He just wanted to keep the remains from being reburied before they could be properly studied, a study, which, he believed would set the record straight. It is Chatters' opinion that the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) is anti-science, and that it was created, in essence, out of an irrational fear by Native Americans, who he says fear their rights as aboriginal Americans are in danger of being taken away by racist whites. Chatters believes that Kennwick Man and all of the other "anomolous" remains are national treasures that should be kept under high security, but made available to researchers freely and forever. The author also explains prevailing theories about human migration to the Americas. He details how early immigrants might have lived, and summarizes known paleoarchaeology of the Northwestern U.S. Ancient Encounters is a bestseller and easily obtained (sells for $15.00, paper) from most chain book stores or online vendors. Anyone interested in the Kennewick Man controversy, or NAGPRA, or the search for the first Americans will want to read this first-person account. Kennewick Man: Perspectives on the Ancient One Edited by Heather Burke, Claire Smith, Dorothy Lippert, Joe Watkins, and Larry Zimmerman Third Coast Press 2009 paperback ISBN# 978-1-59874-348-7 I have to admit, that before I read this book, on issues of the study of human remains, I more-or-less sided with science. I think I understand, now, how different a perspective I had, pretty much from the get-go, from a Native American view of the topic. I am not saying that I completely agree with everything expressed by Native Americans represented in the book, but I am more sympathetic to those opinions and,perhaps, more open minded toward their point of view. This refreshing book dares to place opposing views within the same volume, thus underscoring the polarity of opinions between the involved parties, and allowing the reader to see how difficult it is therefore, to find any possible compromise. The book challenges you to take a stand-- it is not an easy quest. The very first paper, written by David Hurst Thomas, tells the riveting tale of Einstein's brain. What, you say, has this got to do with Kennewick Man? What rights do the dead have? This is the issue at the center of the book... our basically Western European culture has a completely different take on just what the dead are, much less whether they have rights. It is not only just the disposition of a dead one's property that is at stake, but that of the body itself, the remains, that are also defined as property. By the time you finish this essay, you will find you have shifted a bit away from your likely original position supporting science. I'm assuming much about my readers!-- But I'm guessing most of you will not be Native Americans. Nothing about this issue is common-sensical, nor can it be understood through what seems (to those who advocate it) a logical, pragmatic, pro-science, pro-knowledge approach alone. Laws actually define under what situations a person might dig up human remains, and like all laws, are subject to interpretation, mostly surrounding property that might have been interred with the remains. If "important" material remains are the materials the deceased was buried in, then the remains might be disturbed under some conditions interpreted by the courts. But Native Americans hold no such distinctions. The dead are but transformed; they are not dead, at least by Western standards. Their property is still theirs, and their remains are meant to be cared for, or interred, in such a way as to perpetuate their living spirits. There can be, according to the Native writers included within this book, no compromise. The papers in this book deal with important topics-- cultural identity, race, racism, property rights, rights of the dead, and more. Some of the papers are straightforward courtroom transcript of testimony and judicial ruling, others are straightforward telling of Native Ways, as told by Native American spokespeople. There are also scholarly papers, The Case for Science section of the book lays out various anthropological, archaeological and genetic arguments made in court to support futher study of Kennewick Man. Packed into its near 300 pages are 41 papers that cover every conceivable angle of the Kennewick Man controversy. If one truly wishes to understand the complexity of the case and its implications, then this book is quite simply a must-read. It is most certainly the most interesting book to date on the topic. I was told by one of the contributors that this book was originally menat to be published in two volumes, one for each point-of-view. I am pleased that the publishers ignored this idea, and instead, refreshingly, published everything together in one volume. It is both a perfect read, and perfect reference just the way it is. Kennewick Man: Perspectives on the Ancient One, sells for $29.95, and can be ordered direct from the publishers by clicking here. reviewed by Bob Wishoff |

|

The

Reluctant Mr. Darwin An Intimate Protrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution by David Quammen W.W. Norton 2006 paperback ISBN# 978-0-393-32995-7 The Chair of the Anthropology Department at Texas State University-San Marcos recommended this book, and what a delight it is! Not the picture you would imagine of science's most celebrated and controversial figure: Darwin's knowledge of just how controversial his ideas were at the time, made him into a nervous wreck. Author David Quammen paints a protrait of a very human and eccentric Charles Darwin, one who, were it not for his friends, might never have published his famous theory of natural selection. This is a well-written, very focused book-- perfect for a day at the beach. Trust me, you'll enjoy it! Available in paperback for $14.95-- order it direct from the publisher by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Lewis

& Clark and the Indian

Country: As

one of the first and most well documented expeditions into the American

West

from the Mississippi to the Pacific coast, the expedition of Meriwether

Lewis

and William Clark are an essential source for understanding the

aboriginal

backdrop of this part of the continent and the results of this cultural

incursion. With the bicentennial of this

trip in earlier in this century there has been a growing awareness of

the

important contributions to this journey; the valued role of Sacagawea

even

found expression as the face on a dollar coin. This

interaction is generally presented from the viewpoint

of Lewis and

Clark’s Corps of Discovery, one purpose of which was to study these

native

peoples. But

the purpose of this collection of papers is to present from a wider

viewpoint the

influence of this expedition on the peoples and “Indian Country”, an

influence

that extends far beyond the two years of this exploration from 1803 to

1806. Hoxie and Nelson draw upon an

amazing

diversity of sources to illustrate the long lasting effects of this

confluence

of cultures, drawing them into four basic parts. The

first part, ‘The Indian Country’, deals with the Hidatsa, Mandan, Nez

Perce,

Blackfeet and other tribes which would eventually encounter the Corps

of

Discovery. Among others there are

chapters on creation mythology, rituals, lifeways and diplomatic

networks by

tribal elders and later researchers, with a chapter from a Department

of

American Ethnology Bulletin on the role of the newly introduced played

amongst

previously pedestrian peoples thrown in as well. In

the second part, ‘Crossing the Indian Country’, deals most directly

with the

expedition itself, replete with many journal entries and expository

articles

dealing with friendly and not so friendly encounters with the Mandan,

Hidatsa,

Clatsop, Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Umatilla and Blackfeet. There is even

an interesting

opening chapter by Thomas Jefferson, that prime mover behind the

expedition,

dealing not only with his observations on “the Indians of this

continent” but

the mammoth finds at Big Bone Lick and his speculations that such

creatures

might still be wandering about the West waiting to be discovered by

intrepid

explorers. Part

3, entitled ‘A New Nation Comes to the Indian Country’, deals with the

aftermath of the opening of the expedition’s opening of Indian Country

over the

next century. The numerous accounts

here, many of them contemporary, deal with the impact on the natives of

the

newcomers fur trade, settlers, treaties, mining, gold rushes, ranching

among

the tribes, missionaries and schools. The

final part, The Indian Country Today, deals with the outcomes of the

United

State’s intrusion into the Indian Country first opened by the

explorations of

Lewis and Clark. The renewal of salmon

fishing, environmental concerns, safeguarding native tongues from

extinction,

preserving native cultures and ‘The Meaning of the Lewis and Clark

Bicentennial

for Native Americans.’ A

retrospective conclusion, ‘Lewis and Clark Reconsidered: Some Sober

Second

Thoughts’, James P. Ronda reflects on the all too readily encountered

bicentennial

misrepresentation of what the Corps of Discovery really meant for this

country,

ours and theirs. “On the road with Lewis

and Clark, or standing alongside the trail as they pass by, we meet

ourselves. More important, we encounter

people who are not us. This is, I think,

the most important thing. On this journey we meet strangeness, just as

Black

Cat, Cameahwait, and Coboway met strangeness. And

this is what I fear we lost in a bicentennial spasm of

self-congratulation and overblown self-importance.

All too often the bicentennial became an

endless round of shaking hands with ourselves. On

too many occasions the bicentennial offered the Little

Jack Horner

version of American history. We stick in

our thumbs, pull out plums, and repeat endlessly what good, bright boys

and

girls we’ve been. We do not learn and

grow by shaking hands with ourselves.” This

is a book with many voices, and all are refreshing to listen to in

their

variety and multifaceted versions of what Lewis and Clark have meant

for Indian

Country. It has few illustrations, but

there are a number of very interesting old and insightful maps that

bear closer

attention, including even “An Indian

Map of the Different Tribes that inhabit

on the East & West Side of the Rocky

Mountains with all the rivers & other remarkabl. places, also the

number of

Tents, etc. Drawn by the Feathers or Ac

co mok ki – a Black foot chief – 7th Feby,

1801” from the Hudson’s

Bay Company Archives. Lewis

and

Clark and the Indian Country is one volume

certainly worth purchasing by anyone that seeks a deeper understanding

of what their great adventure meant

to all of those who inhabited and continue to inhabit Indian Country. This book is a rare and wonderful find,

well worth the $24.95 for the

paperback version. You can order this book directly from

University of Illinois Press website (click here).

reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

Prehistory,

Personality

and Place: Here we have a book about controversy in archaeology, a specific one to be sure, but a book that truly illuminates the kind of debates that scholars pursue in such a situation, as well as the politics and personalities involved in those debates. The main focus of Prehistory, Personality and Place is Emil Haury, a person whom the authors describe as “a real archaeologist practicing real archaeology,” and “an academician who was committed to understanding the unwritten past, who believed wholeheartedly in the techniques of scientific archaeology, and who used his influence to assist scholarship rather than to advance his own career.” Haury is best known for helping archaeology move away from antiquarian practices toward the analysis of field data. Influenced by Alfred Kidder, Haury developed field techniques and strict controls that enabled the gathering of empirical data through excavation. His 1924 book, The Study of Southwestern Archaeology is generally regarded as the first comprehensive archaeological study based solely on empirical data. Haury is also one of the first researchers to master the use of dendrochronology, the absolute dating of tree rings pioneered by Andrew Douglass. Author Reid also had a hand in the penning of an excellent biography available for reading at The National Academies Press website. During an amazing survey season in 1931, Haury would make discoveries that would lead to his description of the Mogollon. Haury would spend over 60 years defending and elaborating the results of this critical survey. At issue were pit house villages, Mogollon (situated on a hill top) and Harris (located in an open plain), that Haury believed exhibited significant variation from what had been observed elsewhere in the area. Haury wrote of the excavations of those sites, that “(e)very day produced new surprises.” Other sites soon produced similar surprises leading Haury to define the Mogollon directly from the empirical observations he and his crew had collected. Criticism soon followed, mostly by those who saw Haury’s evidence for the Mogollon as being, in reality, nothing more than “backwater” Anasazi (or Basketmaker)… in other words, merely a minor variant on what had been observed and categorized previously. Using ceramics and stratigraphy, Haury reasoned that the only “foreign” pottery found at the nearby Snaketown site was all Mogollon. “Thus, at or before AD 700, three broad types of pottery were being made, the black-on-white of the late Basketmakers, the earliest red-painted Hohokam types, and the red-on-brown of the Mogollon.” According to the authors, this was but one of the points that Haury’s critics would return to over and over in attempts to discredit its antiquity. Haury noted that while there was little to compare the Mogollon to the Hohokam, that there were closer comparisons with the Basketmaker. However , Haury concluded that there were nevertheless “elementary differences” in their architecture, stone tools and especially the pottery styles, that allowed for the identity of the Mogollon to be clearly seen. The

major points of controversy critics had with Haury (as noted by the

authors,

and cited from their book) are as follows: Haury’s arguments required a new kind of logic, one that moved away from being exclusively taxonomic in nature. Did

Haury’s view prevail? Even if you know the answer, you will still enjoy

the

intelligently written discussion these authors present. As a

non-archaeologist

reader, you’ll begin to understand the role of personality in

scientific

argument. This book about how researchers adopt and reject new ideas

and

methodologies is a surprisingly good read. Order it directly from the

publishers (paper, $19.95) by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

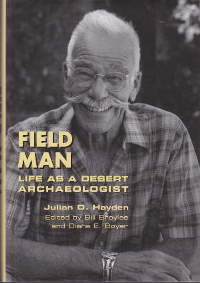

Field

Man:

Life as a Desert Archaeologist

Called the last of the “desert rats,” Julian Hayden was that most invaluable archaeological team member, a competent field man with an eye for detail combined with powerfully developed ethnographic observation skills. Oneworldjourneys.com writes that “Julian Hayden worked the early great sites of southwestern archeology (Keet Seel, Ventana Cave, Snaketown) in the twenties and thirties, then drifted first into carving jewelry and then into installing septic systems and running ditching crews. But one day in the fifties, he entered the heart of the Sonoran desert on a quest of understanding: he began spending every weekend in the Pinacate marking out early man sites, spots he figured showed human signs at least a 100,000 years old. When he finished, he had created the archive of early man in the Sonoran desert; his book, The Sierra Pinacate, captures both his knowledge and love of the place. His gruff, honest manner trained up one more generation of desert rats to probe and protect the place. Now his ashes coat the land he loved. He became one more link of discovery and documentation in the hundred thousand year chain of being here.” Field Man is the most entertaining archaeologist’s memoir I’ve ever read. Here is a book that goes just fine with a cold beer on a hot summer day. It would be the perfect book to bring along to a field school. Editors Broyles and Boyer did an incredible editing job, staying out of the way of Hayden, and just let Hayden’s voice dominate the book. We are not only treated to some inside stories from some of the nation’s most important archaeological sites, but are also given charming and often humorous insights into the author’s personal life. Hayden’s entire life was woven around the Arizona desert and archaeology. His story is interesting whether or not archaeology is your thing. To quote the book’s press release, Field Man is “an evocative recollection of a bygone time and place, a time when archaeological trips to the Southwest were ‘expeditions,’ when a man might run a Civilian Conservation Corps crew by day and study the artifacts of ancient peoples by night, when one could honeymoon by a still-full Gila River; and when a Model T pickup needed extra transmissions to tackle the back roads of Arizona.” Hayden was a self taught archaeologist, but nonetheless worked with some of America’s most esteemed scholars. His book tells us of all of these people in his life with an honest eye and in colorful, descriptive language. Everything is here… Hayden advice: “Never trust an Indian if he gives you a nickname deadpan.”… to how to install a proper septic tank… to his involvement and opinions on the pre-Clovis debate. Hayden’s opinion of archaeology: “I’ve remarked more than once that archaeology never put a dime in a person’s pocket, which is another way of saying that we are on the fringe of what is necessary.” There are lots of provocative and funny comments in the book that you’ll find creeping into your conversations. Order a copy of Field Man direct from the publisher, for $45.00 (hardcover only… email them and ask them to publish it in paper!) by clicking here. You’ll regret having to put the book down until you have read each and every page: a great read! reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

| Home | Gallery | Latest Finds | Back to Main Book Review Index |