|

present Book Reviews For Amateur & Avocational Archaeologists |

|

|

present Book Reviews For Amateur & Avocational Archaeologists |

|

Mesoamerican and

South American Archaeology

Southwest United

States

Southeast United States

Mississippian Complexes

All Other United States

Mesoamerica and South America

International (Europe, Africa,

Asia, Caribbean)

Back to Main Book Review Index

|

| Home | Gallery | Latest Finds | Back to Main Book Review Index |

|

Between

the Lines by Anthony F. Aveni University of Texas Press 2000 1st edition ISBN# 0-292-70496-8 cloth hardback The famous Nasca lines in Peru have been the subject of many a book over the years, but none as interesting as Aveni's title. In explaining his theories of why the lines were made, the author takes us on a global tour of monumental sites across history and the globe. Recounting sites which over the years have been called "wonders of the world," Aveni brings the enigmatic lines into the sphere of the most wonderous creations of humanity. The author, an astronomer, tells us of his journey into the world of archaeoastromomy (he is a recognised pioneer in this field), and how he became interested in ancient buildings which act as pointers to important astronomical events critical to ancient societies. Perhaps it was inevitable that he would, sooner or later, become involved in the investigation of the Nasca lines. The lines have an interesting history--- ignored by most archaeologists, and burdened by explanations Aveni felt had not been either thoroughly thought-out or poorly researched, he quickly became hooked and spent years walking evey inch of the Peruvian pampas looking for a more logical rationale for their existence. We are presented with a most wonderful adventure! Aveni focuses on the idea that to really understand the lines, investigators needed to change their basic point of view--- it is impossible, Aveni writes, to explain a phenomenon like the lines while looking at them from a modern perspective. He felt that while the lines were possibly tied to astronomical events, that their function would be most likely found by studying the anthropology of the Nasca ancients to see how their society's structure would allow for the creation and function of the lines. And so, Aveni articulates the entire history of the region, cleverly, I might add, taking the reader through a well-woven, well thought out summary of events which focus not only his approach, but the ideas of other researchers throughout the ages. Aveni shows the reader how multiple sources of information can provide the little clues a researcher needs to find a new thread of inquiry, as well as how they can be used to debunk previously accepted broad conclusions. Aveni articulates the unique social structure of the ancient Peruvian and Inca cultures, one based upon a radial concept, called the ceque system--- lines! Community projects shared by creating radial zones based upon bloodlines and craft begin to indicate completely new viewpoints of why the Nasca lines exist, and how they were used. The author then shows us how he proved his assertions through well-written and illustrated summaries of his work which countered the most prevalent astronomical explanations. Quite simply put, this is the definitive book on the Nasca lines and a must-read for those who have been fascinated by this true "wonder of the world." This excellent book, which usually retails for $39.95, can

be ordered

direct from the publisher at a discounted price of $26.77 by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

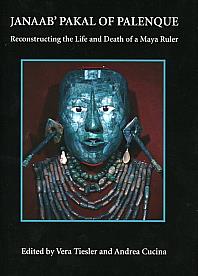

Janaab’

Pakal of

Palenque Reconstructing the Life and Death of a Maya Leader Edited by Vera Tiesler and Andrea Cucina University of Arizona Press 2006 1st ed. ISBN# 0-8165-2510-2 cloth hardback The discovery, in 1952 by Alberto Ruz Lhuillier of the tomb of Janaab’ Pakal, created a sensation and was one of the most famous archaeological discoveries since Howard Carter found the tomb of Tutankhamen. In the Prologue, author Sergio Raul Arroyo quotes Ruz’s feelings upon discovering the tomb: “Out of the dark shadows emerged a fairy-tale sight, a fantastic and transcendental view of another world. It looked like a magic cave sculpted out of ice, the walls shimmering and bright like crystals of snow… It gave the impression of an abandoned chapel. Bas-relief stucco figures were walking along the walls. Then my eyes looked at the floor, which was taken up by a huge, perfectly preserved carved stone.” Despite a seeming wealth of data analyzed as a result of the first excavation, there was much that could be re-analyzed using more modern techniques. For example, it was thought that Pakal died well into his eighties, a rare thing in those days, and that he had a club foot, or was deformed in some way. There was much deterioration on Pakal’s remains, however new techniques for facial reconstruction, and other improvements in osteological and dental analysis held forth hope that these and other questions about Pakal could now be answered. It turns out that many assumptions have been made regarding the lives of Maya rulers--- "researchers all too often find what they expect to find." This book is much better than any TV episode of either "Bones" or "CSI" could ever be. I found the items about dental analysis and the diet of the ruling class very interesting and informative. By the way, it turns out Pakal had indeed lived at least into his fifties, and that he did not have a deformed foot. And what of the mysterious “Red Queen,” a burial that came as a complete surprise to the site’s discoverers: just who was she, and why was she interred with the aged ruler? Trust me, you will read on. An amazing amount of information is packed into this volume: epigraphic studies, physical anthropological studies, histomorphometric and taphonomic analyses that provide unparalleled insight into the lives of the ruling classes of Maya culture. The book’s eleven papers answer long-standing questions and also pose some new ones. A thirty-three page bibliography ends the book, also providing the researcher with countless leads to more information. Whether you are interested in the archaeology of the Maya or in physical anthropology, I believe you will find it a very satisfying read. Order Janaab’

Pakal

of

Palenque direct from the

publisher,

for $50.00, by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

FEATURED AUTHOR: GARY

URTON "Dr. Gary Urton is Dumbarton Oaks Professor of Pre-Columbian Studies in the Archeology Department at Harvard University. He has decades of experience living in the Andes and has been studying khipu intensely for over 12 years. Dr. Urton has personally recorded spin direction, knot direction, and attachment on hundreds of khipu, augmenting the existing information gathered by the Aschers in the 1970s and 1980s. In addition he has recorded data on many previously unstudied khipu, including the important collection in Chachapoyas." from "The Khipu Database Project" website (be sure to check it out!) Dirtbrothers.org is proud to spotlight these fine books by this important researcher and author! Bob Wishoff, editor Signs of the Inka

Khipu Defining a khipu, author Gary Urton writes, “Khipu (knot; to knot) is a term drawn from Quechua, the lingua franca and language of administration of the Inka Empire (ca. 1450-1532). The khipu were knotted-string devices that were used for recording both statistical and narrative information, most notably by the Inka but also by other peoples of the central Andes from pre-Inka times through the colonial and republic eras and even – in a considerably transformed and attenuated form – down to the present day.” Look to the left and you can see a khipu on the cover of the book If you were to turn the cover picture clockwise 90 degrees, you would see that a khipu has a central cord from which are hung many left-or-right-twisted, colored yarn “pendant” stings (sometimes with their own sub-strings attached).containing knots of 3 distinct types: single knots, long knots and figure 8 knots. Each form of the knots represents number units tied onto an appropriate region: the length of the pendants taken together as an area, is split into regions representing 1’s, 10’s, 100’s and 1000’s. Each of the cords and pendant strings are composed of twisted yarn of many colors. All of these things have their “mirror” images. All of these factors, when looked at together, form the basis of a fascinating “writing” system of representation that provides insight into the minds of an ancient people whose empire was cut down just as it was reaching its prime. We can never know now how this system would have changed over time had the empire been around for a couple hundred more years, but Urton quotes Spanish documents that praise the Inka’s accuracy at accounting, claiming it better than their own bookkeeping. It seems perfectly reasonable that complex commentary could also be encoded in the khipu. Binary coding, while seemingly a straight forward concept, gets properly knotty when applied to yarn—we’re just not used to seeing our textiles as vehicles of 7 bit binary numerical data. But Urton seems to have a way with explanations and so, by the time we get to the even more interesting anomalous khipu (knots not where you might expect them, or containing knots defying knot-type rules), we have been prepared and are ready to understand Social Dualism and Binary Oppositions, which is included in the chapter Sign Theory, Markedness, and Parallelism. Urton shows us just how much possible information could reside in khipu, and suggests that the khipu which do not follow observed rules could be a complex form of narrative yet to be deciphered. He manages to take the reader through near everything which is known about khipu, then addresses comparative issues of language and symbol which suggest all kinds of future research angles. The bibliography, included at the end of the book, has already led me to some great sources for more information. Following the binary way of thinking of this book, I give Signs of the Inka Khipu a hearty pair of thumbs-up. Signs of the Inka Khipu can be

ordered

direct from the publisher, for a web-special price of only $14.71, by

clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

The Social Life of

Numbers: Numbers and arithmetic are taken for granted, but there are broad conceptual, linguistic and cultural underpinnings essential to their application that is not always apparent on the surface; anthropology and ethnography can play an important in our understanding of how non-literate societies evolve the ability to count and abstractly manipulate ideas of quantity. Gary Urton, a specialist in the archaeology of the Andes Mountains of South America, has produced an extensive study of numbers and their usage in the Quechuan language. Quechua was once the language of the Inkan empire and is still spoken as a primary language widely throughout Peru and Bolivia. Urton took on this challenging task initially as “an essential first step in pursuing my primary interest at the time, which was the analysis of the Inka khipus. Khipus are the knotted string devices that were used by the Inkas to record both quantitative data (such as census accounts and tribute records) and information that was said to have been used in the recording and retrieval ---or ‘reading’---of Inka histories, genealogies and myths.” But in the course of his studies he also came to perceive that the cultural mathematical baggage that is carried by modern researchers has the potential to obscure deeper levels of meaning woven into the khipus. The metaphorical and symbolic patterns intrinsic in the language of Quechuan arithmetic may even play a role in embedding not only mnemonic but proto-linguistic qualities into khipus, leading to a broader interpretation of their meaning. In the course of his linguistic research, Urton undertook an intensive study of Quechua, the state language of the Inkan empire which is still widely spoken as the first language throughout much of the Andes, first hand in Peru and Bolivia. His collaboration with Primitivo Nina Llanos, a Bolivian professor of the Quechuan language, led to extensive interviews in the Quechuan language on “such topics as: the verbs to count, add, subtract, multiply, and divide; each number from 1 through 10 (for example…four and a half hours of conversation and analysis of Quechua terms, and their uses, for ‘one’ and ‘first’); terms for quantitative comparisons and evaluations (such a more than, less than, equal to, too much, too little); and a host of other topics that touched –sometimes remotely—on the language of numbers, arithmetic, and mathematics used in a variety of settings (such as farming, weaving, and marketing) in Quechua.” A unique understanding of the numerical principles utilized in weaving practices was obtained by the author’s undergoing a three month apprenticeship as a weaver. This is one of the most interesting anthropological asides in the book, not only because he took on the learning of a craft that was classed as a purely female pursuit (though other locales do have male weavers), but he chose to apprentice himself to the 12 year old daughter of a master weaver. By working with a less accomplished he was better able to discern their utilization of mathematical patterns, an underlying principle that is subliminated as the practitioner becomes more accomplished. Chapters on the use of cardinal and ordinal numbers (cardinal numbers indicate quantity, whereas ordinals indicate position in a series) may at first seem obtuse, but Urton draws out the point that “as elements of ordinal numerals, cardinal numbers are not considered to have any independent existence, much less force, as abstract entities; that is cardinal numbers cannot alone order anything. Rather…in Quechua ideology it is social relations—especially those formed biologically, emotionally and politically within a reproductive group—that constitute the principal sources of order (that is, of hierarchy, succession and so on.) Thus, it is only by coupling the number series with the organizing forces of social relations that ordinal sequences emerge as meaningful, rational, expressions of relations and forces organizing and uniting the members of a group.” Hence, “…because of their ‘exposure’ through metaphors, puns, etc., to virtually the full range of quechua semantic activity, a large chunk of which is drawn from and refers to the world of everyday social (especially kinship) relations, that I have indicated in the title to this work that we are concerned with here is the ‘social life’ of numbers.” This philosophical and metaphorical view of the use of numbers, in Urton’s view, underlies “one feature that clearly distinguishes Quechua arithmetic practice and mathematical conceptions from those in the West…a principle that I will refer to as ‘rectification.’ Simply stated, rectification is grounded in the idealistic, philosophical, and cosmological notion that all things in the world---from material objects to habits, attitudes and emotions---out to be in a state of balance, or equilibrium. Depending on the object(s) in question, ‘balance’ can have, among other forms, a distributive, constitutive, or moral significance.” In other words, the pre-conquest Andeans may have utilized their mathematical principles such as addition, subtraction, division, multiplication, ratios and fractions in such diverse fields as weaving, the manufacture of khipus, engineering, metallurgy, astronomy, agriculture, herding, and economics, but there was always a sense that it was in the pursuit of harmony or re-establishing a sense of equilibrium in their universe. Another concept dealt with by Urton in this book involves the superimposition of a new system of mathematical semantics by Spanish colonialism. “The most obvious and active elements of the political arithmetic of colonialism, in the sense that these were the elements that most directly shaped a new experience of numbers in the post-Conquest Andean world, were: first, the (profusion of) written number signs; and second, a new set of values that lay behind the conception of numbers and the manipulation of those numbers in arithmetic and mathematical operations…the values alluded to in the latter were quite different from those underlying the arithmetic and mathematics of rectification…” This is an area of anthropological inquiry with deep implications for understanding mathematical ontology in preliterate cultures, especially those encountering and ultimately immersed in more Western systems. An appendix of “Quechua Number Symbols and Metaphors” offers some interesting examples of how the written numbers introduced by the Spanish developed subtler meanings related to their shape and resemblance to other objects, many of a frankly sexual nature. Very thoroughly researched and firmly based in the Quechuan experience of what numbers and their manipulations mean for the Quechuan people, this is a profoundly thought provoking book, and one which forms an essential base for much of Urton’s later work on khipus. It is available from the Univeristy of Texas Press for $17.95, and can be ordered directly from their web site for the book here for their Web Special price of $12.02. By following links there one can also find not only the book’s table of contents but read the first chapter online, as well as a links to another related book edited by Gary Urton and Jeffrey Quilter, Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu. And for those interested in learning more about khipus, you can visit the online Khipu DataBase Project (see link at head of this section) established by Gary Urton and Carrie Brezine, with a large gallery of some of the finest surviving examples and links for further articles on them. reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

Inca Myths

Mythology tells more about a civilization than just the legends associated with its culture. Gary Urton, an expert in the field of Andean archaeology and anthropology, has produced a concise introduction into the role of the Incan state in incorporating local mythologies to consolidate their position of power as one of the greatest civilizations of the Americas. The rapid rise of the Incan state, incorporating most of the western coast of South Anerica, was possible largely because of “pre-existing relations, institutions of state, and habits of empire inherited from earlier peoples.” Consequently this book covers mythic components from the Chavin, Moche, Huari, Tiahuanaco and Chimu cultures. These societies were built largely on the thousands of kinship groups known as ayllus. Each ayllu was widespread, distributed over lower coastlands, intermontane and alpine regions. Trade partnerships within these groups facilitated a complementary utilization of the limited resources from each region, binding them into groupings of related mythos that found expression in festivals and reverential inclusion of mummies of previous leaders at communal gatherings. Although individual differences existed, certain recurrent elements, such as a “staff deity” standing between two staffs or possibly corn stalks, are widespread in both art and architecture: present from earliest cultures, they were ultimately incorporated by the Incan state as well. The practice of mummy cults, whereby deceased rulers were maintained in their old palaces and retained all their old holdings, made expansion of territory by new rulers necessary, and this in part gave impetus to the extension of the kingdom of the Incans into the ‘four quarters’ of their Andean empire. The origin myth of the Inca people was meant to cement the rise of their ancestral nobility and rulers, centering on their emergence as four brothers and four sisters from three caves on the mountain of Tambo T’oco and their alliance with the ten local ayllus. From there they moved north to what was to become the capital city of Cusco, their leader Manco Capac emerging over a mountain at sunrise. Garbed in plates of gold ablaze in light, he came to rule as the “Son of the Sun”, establishing the rule of 12 following leaders, a lineage that finally came to an end with Atahualpa, whose murder by Francisco Pizarro finalized the fall of the Incan empire. It is through the filter of Spanish colonialism that most of our understanding of Incan mythology has come to us, and, as Urton clearly points out, many of these early chroniclers of their traditions were interpreting them to enhance their “view that the Inca dynasty represented a tyrannical regime that had essentially gained power by fraudulent means”. However, a sizeable number of the early works on preliterate Incan history and mythology were written by native Quechuan speakers. The particularly harsh imposition of colonial Catholicism also led many of these early local narratives to put a hopefully favorable spin on their cosmological viewpoints, leading to debatable descriptions of a triune deity and Christ-like qualities in a character known as Viachocha in Andean religious traditions. Published in a joint cooperation between the British Museum

Press

and the University of Texas Press, this book is brief but very nicely

illustrated.

Gary Urton’s extensive background as a leading scholar in the area

lends

such a succinct clarity to the subject that serves this books serves as

an excellent synopsis of Andean prehistory as well as its mythic

underpinnings.

It is available for the “Web Special” price of only $8.68 from the

University

of Texas Press website for the book, located here. reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

Precolumbian

Water

Management Ideology, Ritual and Power Edited by Lisa J. Lucero and Barbara W. Fash University of Arizona Press 2006 1st ed. ISBN# 0-8165-2314-2 cloth hardback Everywhere one looks in the pre-Columbian world, there are bodies of water with special meaning. The public’s perception of these are filled with sensationalist images of young virgin “princesses” shoved over a precipice into the cold cenotes, sacrificed to the Gods. Precolumbian Water Management seeks a little more depth (no pun intended) in the topic, with a collection of fourteen excellent papers designed to show the place of water systems within the mental language of the ancients. Water management was precious for survival in the ancient world, leading many to theorize its place in actually forming the heart of civilization, the motivations for it. “Although important and insightful works on water symbolism and hydraulic engineering have pre-dated our effort in diverse areas, such studies have never been brought together in one cohesive volume before.” Delivered in chronological order from the pre-classic through to the post-classic eras, the books papers show that leaders “(e)ven if (they) do not act as water managers, are heavily involved in propitiating supernatural entities for everyone. It is this latter role that largely gives them power over others and the resulting ability to exact tribute. Leaders are responsible not only for performing key water rites but also for providing capital to repair water systems damaged by flooding or heavy rainfall. If these responsibilities are not met, political leaders often lose the basis of their power: the labor of others.” The authors brilliantly illustrate the significance of the locations of buildings and how these locations built upon sacred traditions to further emphasize the power of water, and further, how different cultures adapted their water traditions to suit their environments. Perhaps the most interesting conclusions made from the papers concern the comparisons between Southwestern cultures and Mesoamerican cultures. The papers show a definite scalability factor which has perhaps has hidden the equal complexities exhibited by both sets of cultures.Though the book focuses more on Mesoamerican cultures, there is a definite linking to the classic works by Haury and others on the critical force of water as a spiritual and political unifying factor as well as economic necessity. The volume is packed with ethnographic and archaeological evidence for all of the theories expounded upon, and finishes up with a nearly fifty page reference section. Precolumbian Water Management

can be

ordered direct from the publishers, for $55.00, by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

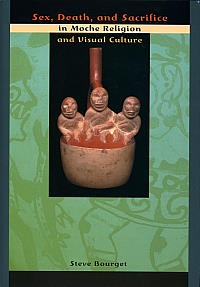

Sex, Death

and

Sacrifice in

Moche Religion By Steve Bourget University of Texas Press 2006 1st ed. ISBN# 0-292-71279-0 cloth hardback The Moche were a sophisticated culture, probably the first state-level society in Peru. This complex society left no written language, yet created one the most sophisticated iconographic representational systems in the region. Moche ceramics portray a wide range of realistic and anthropomorphic animals, as well as some of the most interesting portraits of people engaged in daily and ritual activities. Many of the ceramics show people either disfigured or as skeletons, and many represent sexual activities. Access to most of the ceramics was restricted to the elite class. Bourget undertakes to explain these ceramics within the contexts of the archaeological remains of human sacrifice and burial rituals. He does this first by introducing the reader to several “processions” or line drawings representing “ritual drama”. He postulates a reference to these processional characters in ceramic iconography, such as one he names “Wrinkle Face”, a figure which occurs regularly both in line rendering and in portrait ceramics, and further postulates a rationale for the association of sacrifice and sacrificial victims with the processional characters. It is not an easy task to explain a sexuality isolated from what might be seen as cultural norms—it is unlikely we will ever know what the Moche people thought of certain sexual acts, or what sexual acts were considered normal or what place sexuality in general had within the context of normal Moche life. However, Bourget makes an interesting case for each and every scenario shown within the limited (looting has truly taken its toll on Moche archaeology) collections available as well as material contexts of those available ceramics. Bourget also examines the other details present on various ceramics, such as ritual items, their meaning and placement on certain ceramics. Motifs also play an important role in the author’s theories--- wave motifs and stepped-stair motifs all have their explicit meanings when paired with either a mutilated portrait figure, or with figures engaged in sexual acts. After establishing a connection between the ceramics’ iconography and sacrifices and burials, Bourget then argues that a great deal of information regarding Moche beliefs regarding the interaction between the worlds of the living and the dead are also represented within the assemblage of ceramics. An interesting and sometimes disturbing book, it will

nonetheless

fascinate most readers. Copiously illustrated, Sex,

Death

and

Sacrifice in Moche Religion and Culture can be ordered

directly from the publisher, and bought for a special price of $40.20

(a

significant discount over the $60.00 retail price), by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

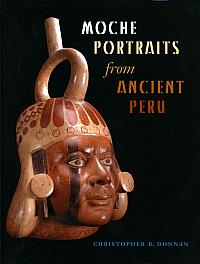

Moche

Portraits

from

Ancient Peru The exquisite pottery of the Moche civilization on the western coast of South America constitutes some of the world’s most amazing examples prehistoric art. This is especially true of the surprisingly lifelike ceramic human heads they created in the 5th and 6th century, the work of artisans so skilled in rendering these realistic portrayals that they are considered by some to be the crowning achievement of their culture. Little known outside of certain art collectors and archaeological scholars, these beautiful works of ceramic expertise are the subject of this wonderfully illustrated book by one of the world’s leading experts on the Moche, the anthropologist Christopher Donnan. This is a book for the eyes, as well as the mind. Donnan has searched through museums and private collections and photographed some of the finest examples available. The resulting high quality prints give this volume the feel of a fine art book, while the descriptions of the Moche culture in which it evolved offer a satisfying background of their purpose. Fine line drawings of this ceramic portraiture in contemporary use from other bits of Moche pottery offers some hint of their role in society; this is especially important since the provenance of most of these existing portraits lies in question, more the result of grave robbers and looting to satisfy private collectors than primary archaeological research. What does seem clear is that one of the primary uses of these ceramic pieces is indeed portraiture. There are series of them which clearly portray the same individual at various stages in their life. Otherwise identical heads are found with widely varying finished and decorations. They were also clearly used as bottles and jars, mostly of the stirrup bottle type, possibly in the consumption of chica, that potent maize beer still in wide use throughout the Andes. Mold matrices were used in the later stages of Moche civilization for mass production of some of the pottery portraitures. A series of photographs details the steps involved in manufacturing from these molds, including the addition of the various stirrup styles found. Although some of the vessels found have been unfinished, the glazing, burnishing and firing techniques involved in finished ceramic portraits is also addressed. Though Donnan makes it clear that he presents only a small sample of the various extant pottery portraits and that much more work needs to be done, he does a fine job of summing up not only what is currently known about them, but also what awaits further research into these fascinating artifacts of Moche culture. This is not only the finest book out there on the subject, but is available for the surprisingly low price of $26.77 when ordered from the University of Texas’s website. (List price is $39.95, more in keeping with a book of this size (8.5x11 inches) and quality, with over 258 color photos and 52 line drawings, cloth-covered hardback, 202 pages of heavy stock.) Interested readers can also visit this site to read the book's first chapter and examine its table of contents. Both the avocationalist and more serious student of archaeology will enjoy browsing their on-line catalog!reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

The

"Popol Vuh," written in K'ICHE'-MAYA (a Mayan language) but a

European script, is the most substantial surviving account of the Maya

view of

their own history, including that of their gods and divine ancestors,

cosmology, and culture. In essence, it is the Mayan Bible. However,

this

manuscript has presented a host of problems for translators. This

electronic

version of the Popol Vuh, translated by Allen J. Christenson, is

probably the

most definitive edition to date. It is difficult to imagine a better

version of

the "Popol Vuh" than this one. It is literary, it is scholarly, and

it is well written by a man who knows his subject. Allen J. Christenson

has

much experience with the study of Pre-Columbian culture and

interpretations. In

addition, he has studied amongst the present day Mayans and speaks

K'ICHE'-MAYA. While Dennis Tedlock's

version is good, Christenson’s translation, format, and overall

presentation

is beyond excellent. Additionally, this

digital edition provides more in regards to technical and scholarly

research.

The introduction provides a detailed history of the Quiche Maya and the

Popol

Vuh. It also includes a history on the original manuscript, the authors

of the

Popol Vuh, parallels with other texts, an analysis of the poetic nature

of the Popol

Vuh, and a translation of the Maya text in modern orthography. Especially noteworthy is the inclusion of the

English

translation with notes, a literal translation from Quiche, a Spanish

translation, a Quiche version that is accompanied with high resolution

images

of the Newberry Library Popol Vuh manuscript, as well as a complete

audio

version of the text read by a native Maya speaker.

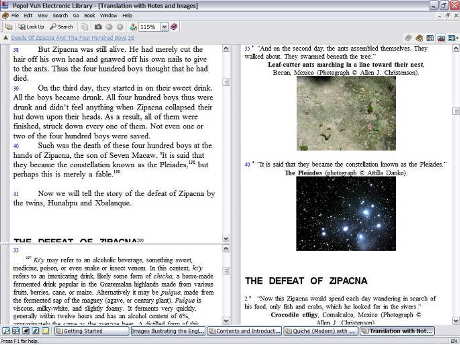

This CD-Rom is a

complete fully searchable

electronic database and contains a guide to the

pronunciation of Maya words, cross-linked texts, Mayan art and images,

illustrations, and audio files related to the Popol Vuh.  Screen shot: All 3 windows will

auto-scroll along with your reading.

Overall, it could be said that the Popol Vuh provides incredible insight into the world of the ancient Maya and their modern descendents. If you're interested in Maya studies and you haven't read this text yet, then you haven't even gotten started. As time goes on it becomes more and more apparent that this book is our guide to understanding Maya iconography, cosmology, and culture. This electronic edition of the Popol Vuh is essential for serious students of Maya culture and history. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Maya can be ordered direct from the University of Texas Press by clicking here. Though it retails normally for $39.95, order it over the web for only $26.77. |

|

The Olmecs: America's First Civilization By Richard A. Diehl Thames and Hudson 2005 1st papberback ed. ISBN# 0-500-28503-9 Perhaps the reason most people do not know much about the Olmec people is that only 20 years ago, it would seem no one knew much about them! This book is a real eye opener. The Olmecs are not only America's oldest civilization, but are the "Mother Culture" for all of Mesoamerica. Richard Diehl is a respected researcher and excavator of sites across Mesoamerica, and his text is both a good read and enlightening. Diehl shows the reader the basis for Olmec civilization, and explores daily lives of the people, both elites and regular folk. Of particular interest are the chapters about La Venta, San Lorenzo, and Chalcatzingo, several of the finest Olmec sites. The Olmecs have been known generally ever since the 1940's, when the finely sculpted giant stone heads most associated with them were first found. We still do not know exactly how these amazing people transported these and other monumental stone sculptures nearly 100 km from the source of materials. Profusely illustrated, this book will fuel your curiosity about the Olmecs; as such, it is well-indexed for for those of you who wish to further research the information presented. Though a paperback, the book is thick stock bound, and all of the pages are printed on high-quality slick paper--- it's a good deal for $22.50. Thames and Hudson have a worldwide reputation for their high-quality books. Order The Olmecs, direct from the publisher, by clicking here. Be sure to check out the other books on their website! reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Maya

Calendar

Origins Dr.

Rice calls this book a "prequel" and an

"outgrowth" of her previous volume, Maya Political Science: Time,

Astronomy and the Cosmos. In

it

she

proposes that the Maya practiced "may" cycles wherein "divinely

sanctioned geopolitical capitals" shift over 256 years.She calls the

book "an exploration of Maya time with a capital T". Rice further

writes that "(i)t is widely known that the Maya posessed astonishingly

accurate systems of recording time (Time) in a series of intermeshing

cycles" and that archaeologists take this for granted. Worse, they fail

to "incorporate the role of the calendar and calendrical

celebrationsintot heir interpretations of Mayan history." The author

claims that archaeologists do not act on their knowledge that the Mayan

rulers were called "The Lords of Time": they do not seem to really know

what the phrase means or what the implications of it are. Rice takes

on a different approach to Time. Linda Schele and David Freidel write

about the "Classic Maya cosmos, creation, ritual, and rulership from an

explicitly astronomical viewpoint, noting the relations between planets

and stars (especially Venus), constellations, the Milky Way, and so on,

as they relateto rituals of creation and as the Maya would have

experienced them in the night sky." Rice explains that "I am less

preoccupied with the explicit animation or personification of celestial

bodies and their relation to classic gods and more interested in the

development of the calendars and their use in framing the

legitimization, of kings and cosmic order." Maya

Calendar Origins is an interesting and controversial book that any

student of Maya civilization will find interesting. The book covers the

entire known history of the Maya, integrating data from anthropology,

archaeology, art history, astronomy, ethnohistory, myth, and linguistics. I found the chapter on the Middle

and Late Preclassic most informative. Order this book directly from the

publisher for a bargain price, only $18.73, by clicking here.

Read the Table of Contents, Preface and

more at the UT Press website! reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

The Teotihuacan

Trinity I

still remember my first sight of

Teotihuacan when I was still a small boy and my amazement at how little

was known of this magnificent place. Legends aside, Annabeth Headrick

has written a comprehensive and fascinating account of the daily life

of this ancient city all based upon an analysis of Teotihuacan's art

and architecture. Headrick

challenges the idea that Teotihuacan was a peaceful place to govern,

instead explaining that there were actually three competing factions:

rulers, military and kin-based groups. Relationships between the rulers

and the military, called a marriage of convenience by the author,

kept them in power and created an environment of warfare. "While the

military may have risen as a necessary part of establishing a new city,

its later manifestation when Teotihuacan was at its apogee reflects an

urgent need to counteract the oppositional forces of the other elements

of the triad. Inherent tensions between the ruler and the powerful

lineage headswould have been rife with detrimental effects." The

military defused such situations by "engaging otherwise antagonistic

parties into a common service that engendered a Mesoamerican form of

civic responsibility." The author

explores the orientation of ritual structures and shows Teotihuacan to

follow patterns common to other Mesoamerican cultures. One such

arrangement is called "triadic" and relates to the three stones

believed to have been placed at the "heart of the world", one of the

first acts of creation. Headrick explores another similar patter in the

"three mountain motif" common in Teotihucan art, which she argues

represents a link to the creation story and not a topographical

allusion. Her section on butterflies and the afterlife, and her

references to "architectural butterflies" are very interesting reads.

Headrick uses Teotihuacan's art and architecture to show how rulers

allied with the military to keep a tight hold on power, power that

wealthy families were constantly trying to usurp. The Teotihuacan Trinity will

be a welcome addition to any library. Mesoamerican scholars will be

citing this important book for some time to come. It can be ordered

direct from the publisher in hardback, for $55.00. A direct link to the

publisher's pages for this book is here--

order The

Teotihuacan

Trinity online for

only $36.85, one-third off! reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

White

Roads of the Yucatan: Changing Social Landscapes of

the Yucatec Maya reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Tlacuilolli:

Style

and

Contents of the Mexican Pictorial Manuscripts with a Catalog

of the

Borgia Group

This edition can be ordered directly from

the publisher for $75.00 by clicking here. |

|

The Art and

Archaeology of the Moche An Ancient Andean Society of the Peruvian North Coast Edited by Steve Bourget and Kimberley L. Jones University of Texas Press 2008 1st ed. cloth hardback ISBN# 978-0-292-71867-8 The culture who built the monumental Huacas de Moche was named by excavator Max Uhle in 1899. The Moche culture occupied an area of the Peruvian North Coast during the time period known as the Early Intermediate Period (AD 100-800). The Moche are well-known, not only for their monumental architecture, but also because of their distinctive ceramic and metallic art forms fashioned with meticulous craftsmanship. Though the culture's archaeological sites have been heavily looted, there have nonetheless been some extraordinary discoveries in the region. This book is a collection of fifteen papers that promise to catch the reader up to the present state of Moche research, "its advances, and problematics." All but one of the papers were presented at at a 2003 symposium (of the same name as the book) held at the University of Texas at Austin. Papers cover a full range of disciplines from iconography and metalurgy to genetic research and textile production. There is simply not a bad chapter in the book. This review will give but a tiny slice of the interesting data and discussion presented by the editors. Elizabeth Benson shows how archaeologists have recovered material remains that are physical manifestations of objects depicted within Moche iconography. When real objects are examined and compared against their representations as motifs in ceramics and architecture, for example, reseaqrchers can infer how much of the iconography is "pure" represntation, and how much is "shorthand" philosophical concept. As an example, she explores the war mace, both as physical object and as symbol, and finds that the mace, like many other representations in Moche iconography, represent shorthand for broader ideas-- hence, the mace also can be shorthand for spirit and power, rather than merely representing its literal "brute force." Subtle differences in this shorthand meaning can reveal differences within a society, and Benson posits that there were indeed differences between northern and southern Moche that are only now coming to light. Christopher Donnan presents a fascinating paper on Moche masking traditions. The Moche had three forms of masks: those that were worn by the living; those that were worn by the dead; and, those made to animate cane coffins. In the latter, masks were used as part of a larger set of elements used to decorate a coffin-- head, arms and legs together create the illusion of a person both "inside and outside" of the coffin. With chapters entitled "Forensic Iconography: The Case of the Moche Giants" (by Alana Cordy-Collins and Charles F. Merbs), and "Spiders and Spider Decapitators in Moche Iconography" (by Nestor Ignacio Alva Meneses), who could resist reading this book? The book is full of color photographs and illustrations. The Moche culture is incredibly interesting, and this book presents the most comprehensive and detailed examination available today-- I highly recommend it! The Art and Archaeology of the Moche can be ordered directly from the publisher ($65.00, hardback), by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Prehistoric

Mesoamerica, Third Edition Mesoamerica is

a complex mix of cultures and peoples whose histories overlap and merge. Each one is distinct from the other and yet

influences

the other across time and space. Scholars

spend entire careers studying each of these

varying peoples and

their rich history and culture. Richard E. W.

Adam’s recent release of a third edition to his popular synthesis of

Mesoamerica is a welcome addition to the specialized literature in the

field. More than a brief overview, this

book provides a detailed look at the civilizations of Mesoamerica and

offers

insight into their varied heritage. He

says the goal [of the book] is

simple: to present an up-to-date

interpretative synthesis of Mesoamerican prehistory.

It is intended for the student as well as for

the curious person who has somehow become intrigued with the past

civilizations

of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. Each section is well researched, offering a

starting point for in-depth study. This is an

excellent book for those with a general interest in Mesoamerica. Adams introduces each civilization

chronologically, illustrating the evolution and flow of ideas as new

cultures

rise from the ashes of earlier civilizations. As

expected,

the

Olmecs, the Maya, and the Aztecs are

covered

in-depth. He documents their social

structures, their daily lives, their living habits, and their

politico-religious

systems in great detail. Less well-known

cultures, such as the Totonac and Huastec are also documented in as

thorough a

manner as possible. The difference in

treatment

is not an oversight of Adams, but rather due to limited archaeological

research

and conflicting historical accounts. For

new students of the discipline, the copious scholarly references

provide an

excellent place to begin more detailed research. Mesoamerican Prehistory Third Edition

is a

well-researched, engaging introduction to the wonderful complexity of

Mesoamerica. It can be ordered

directly from the publisher-- it is currently ON SALE for $29.66

-- by clicking here. reviewed

by

Spencer

LeDoux

|

|

A Sourcebook of Nasca Ceramic

Iconography This

book represents the only attempt to compile a complete dictionary of

Nasca

iconography in English to date. Written

by a leading expert in the iconography of Nasca this volume is an

essential

source for any student of Nasca ceramics. Proulx

beings

the

book by giving the essential information

on the

effects of the environment, political organization, subsistence,

settlement

patterns, and of course the Nasca lines, upon the culture of the Nasca. This is followed by a short description of

the chronology of Nasca ceramics. The

real meat of this book is the extensive treatment of the different

themes found

in Nasca iconography and the interpretations that are associated with

those

designs. These themes, such as the

killer whale and trophy heads, are traced from their origins in the

Paracas

Culture through the collapse of the Nasca culture.

There is extensive coverage given both to the

painted designs and the effigy vessels that compose the Nasca ceramic

repertoire. These designs are illustrated

with ample

drawings and color plates which make this book visually stunning at the

least. Proulx

ends his book with an examination of how iconography helps us in a

modern world

get a better idea of the lifestyle of these ancient people who only

left traces

of culture for us to interpret. Although

we will never know the full meaning of Nasca iconography, through

coupling

archaeology and iconographic study we can build a stronger

understanding of the

past. This fine book sells for

$59.95 and can be ordered directly from the publisher's website by

clicking here. |

|

The Ancient

Andean Village: The Ancient Andean Village: Marcaya in Pre-Hispanic Nasca can be ordered directly from the publisher ($50.00, cloth hardback) by clicking here. |

|

Aztec City-State

Capitals Michael

E.

Smith's

Aztec City States takes a systematic look

at the archaeological and

historical accounts of Aztec cities outside the primary imperial Aztec

capital

Tenochtitlan. Drawing from an abundant array of resources, such as the

historical record, pictorial codices, reports from chroniclers and

conquistadors, colonial documents, and the archaeological records,

Smith

provides a detailed account of poorly known archaeological and

historical data

on Aztec city-states or altepetl’s. Additionally,

the author recounts how various cities and dynasties were founded in

terms of

lineage identification, Aztec concepts of urbanization and city

planning,

administrative organization, and rituals associated with city

establishment.

Furthermore, Smith provides a detailed account of typical types of

public

architecture and urban townscapes. These forms of public architecture

and urban

landscapes are then discussed in terms of meaning within Aztec religion

and

ideology. Drawing from these detailed descriptions,

smith examines the functional role of these cities within the broader

Aztec

empire. In this regard, the author discusses the various functions that

Aztec

city states had, such as farming and food supply, craft production,

markets and

commerce, religious centers, and education. From

these

data,

the author presents a new

argument for the political and religious nature of Aztec urbanism.

Specifically, Smith argues that Aztec cities were deliberately

constructed as

expressions of the political and ideological actions of specific kings

and

nobles. Additionally, as opposed to the commonly held view that cities

were

direct expressions of cosmology, ideology, and religion, Smith implies

that

Aztec cities and urbanization were primarily driven by individual

political

ideologies and not modeled after the central imperial city

Tenochtitlan.

Furthermore, the author suggests that these cities were in fact

co-dependent

upon one another and developed independently, but had mutual

interactions that

ultimately became integral to the infrastructure of Tenochtitlan and

the Aztec

Empire. Michael

Smiths

book

provides an

intriguing and fresh look at the political and social dynamics of the

great

Aztec empire. His methodology in emphasizing the function of individual

cities

within a world-systems approach provides a much clearer picture of the

social,

political, economic, and religious organization within a regional

social

context. Such a method clearly provides a better understanding of the

interplay

between elites and commoners within various Aztec city-states, as well

as the

commercial infrastructure that maintained the Aztec Empire. Overall,

the

detailed and abundant array of information provided in this book is an

invaluable contribution to Aztec literature. Aztec City

States is an enjoyable read that is most definitely

recommended to any reader or scholar interested in Aztec development or

even

urban planning. Aztec city States can be ordered directly

from the publisher (27.95, paperback) by clicking here. |

|

Elite Craft Producers, Artists,

and Warriors at Aguateca: Lithic Analysis Aguateca is a

significant site because it was one that was abandoned. Under attack,

the entire city was left with most everything in place-- a rare

opportunity to see a Mayan city as it was lived in, and from all

classes of life, elites and commoners. Imagine, an entire city

encapsulated on its last day of existance-- sounds a lot like Pompeii--

indeed here we have an unparalleled record for Mesoamerica. This volume is

the second in the Monograph series that is investigating the site. This

volume is the result of what is usually a limited study of Classic Maya

elite craft and artistic production. Aoyama uses his research to

propose that classic Mayan elite men and women artists and crafters

played multiple social and economic roles, implying a more flexible and

integrated system than previously observed. This is an

important book in an important series about a significant Mayan site,

and as such, should not be left out of any student's

library. Order

this book direct from the publisher ($60.00, hardbound) by clicking here.

Volume

1

(Burned Palaces of Aguateca) and Volume 3 (Life and Politics

at the Royal Court of Aguateca) are forthcoming and upon publication,

will also be available at the University of Utah website. reviewed by Bob Wishoff |

|

Veiled

Brightness: A History of Ancient Maya Color By

Stephen Houston, Claudia Brittenham, Cassandra Mesick, Aleandre

Tokovinine, and

Christina Warriner University

of

Texas

Press 2009 1st ed.

ISBN# 978-0-292-71900-2 This

interesting book details a topic not often seen in the literature,

namely that

of the history and nature of the use of color in ancient art, in this

case,

specifically, colors used in the art of the Ancient Maya. Despite the

presence

of color everywhere in the Mayan sites, the authors note that it “is

all the

more surprising … that color is nowhere treated as a subject fit for

concentrated study”, but instead “only as an incidental feature that

requires

description, perhaps, but not in a discussion of motive, intent, or

effect.”While

some of the reluctance to publish works centered around color have been

economical (printing colors accurately costs money), the authors note

that the

provenience of most studies are with art-historians, and that most

academic

departments seldom are interdisciplinary, and therefore even ceramics

studies

seldom focus on aesthetics that “reduce Maya color usage to minute

variation…

that… misses the overall sense of coherence and pattern that can, and

does,

coexist with variation”, a process that misses

“the overall shimmer of unitary design and a

collective desire …

to portray, share, and communicate.”What follows is a book that covers

every

aspect of “color” as it is used within the Maya culture, a book that,

as the

authors agree, will surely open doors--- they invite critique from the

reader. The

book begins by articulating how the Maya “see” color, i.e., the

theoretical

ideas of what colors mean within the Maya society--- were these

concepts

static, or did they change over time? How they named colors is another

interesting point-of-study, and the authors focus on terms used to

describe

colors (by the Maya), simple to complex, and on how they are organized.

Interestingly, the authors point out how the organization of color

arose from

the observation of rainbows. This would seem to be an obvious

concept—that

rainbows offer a straightforward organization of the color spectrum—but

the

Europeans squabbled over this idea for centuries. The

chapters on “Making Color” and “Using Color” are equally thoughtful

contributions. In “Making Color” we learn of the materials used to

create

colors, and find that there is much more to their manufacture than the

sum of

all of its ingredients might imply—many of the skills and processes

involved

are just now beginning to be understood. The wide range of materials

needed may

surprise the reader. In “Using Color”, the authors suggest a

“correlation

between social change and shifts in color technologies and aesthetics”,

and conclude

that “ancient Maya color useage travels full circle”, beginning and

ending with

“ a profoundly restricted, deeply symbolic color vocabulary.” Although

the

particular colors change (the trio of red, black and white, replaced by

blue

and black), “the main focus is on representing the gods; color and line

are

united to imagine the appearance of the divine.” reviewed by Bob Wishoff |

|

Lord Eight Wind of Suchixtlan and the Heroes of Ancient Oaxaca: Reading History in the Codex Zouche-Nuttall By Robert Lloyd Williams University of Texas Press 2009 1st ed. ISBN# 978-0-292-72121-0 cloth hardback

I have had the distinct pleasure of attending several lectures by Dr. Williams and am pleased to review this interesting book. The author, who is also a former bishop, is no stranger to the meanings of visual iconography, and therefore well-placed to be a scholar and interpreter of the pictorial language of ancient Mesoamericans.

In Lord Eight Wind, he shows us how Mixtec scribes recount the life of one of their rulers, Lord Eight Wind Eagle Flints, who lived from A.D. 935 – A.D. 1027. The biography exists as a codex, a type of book fashioned by Mesoamericans. As most of them were destroyed by Spanish invaders, the few still in existence are among the rarest documents on the planet. Scholars have been studying the codices for years, and some of the interpretations have shifted in meaning.

Williams explores one of the eight surviving codices, the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, a detailed history and royal geneology that is nonetheless puzzling in the way that it is presented. Mixtec narratives are not written in a fashion easily understandable to audiences from “outside” of the culture they were intended for. In this book, Williams presents a new methodology for separating timeless mythology from linear history, and is successful in extracting an understandable narrative from the seeming chaos of the codex. The author also provides cross-referencing from other sources and thus is able to present a context for the history of this ruler as never before available.

William's

book brings to life many interesting figures from Mixtec history and is

an

interesting read for nearly everyone: both scholars and the interested

general

public will find something to start a conversation with… hmmm; I wonder

if

there could be a film made someday about this enigmatic ruler? Order Lord

Eight Wind of Suchixtlan direct from the publisher by clicking here. While

this

clothbound hardback originally retailed for $60.00, order online and

get it for

only $40.20! reviewed

by Bob

Wishoff |

|

Andean Expressions Art and Archaeology of the Recuay Culture by George F. Lau University

of

Iowa Press 2011

1st edition paperback

When you think of Central Andean archaeology, you probably find yourself thinking of cultures that existed on the coast of Peru: the Moche and Nasca. The focus of study for this book is the much less well-known Recuay culture located in Peru’s north highlands from A.D. 1 to 700. The Recuay are best known for their distinctive art style, but the author presents us with much more than a comparative art study. More importantly, Lau illustrates the complex relationships that evolved around the Recuay way of doing things, a coherence he calls “Recuayness.” It is this hard-to-put-your-finger-on quality, expressed as shared culture, that diversified and had an impact on history, and, according to the author, that still has relevance today.

This first-ever published study of the Recuay is copiously illustrated with both color and black and white photographs and drawings. Students wishing to do further research will appreciate the bibliography. This is a very important volume of paramount interest to anyone studying Andean cultures. Order it direct from the publisher ($39.95, paperback) by clicking here.

reviewed

by Bob

Wishoff |

| Home | Gallery | Latest Finds | Back to Main Book Review Index |